Tax rules on wealth imbalance and the investigation of money laundering in Peru

Las reglas tributarias sobre desbalances patrimoniales y la investigación del lavado de activos: el caso peruano

Regras tributárias sobre desproporções patrimoniais e investigação de lavagem de dinheiro: o caso peruano

Fecha de recepción: 2021-11-21

Fecha de evaluación: 2022-10-18

Fecha de aprobación: 2023-01-30

Para citar este artículo/To reference this article/Para citar este artigo: Llaque, F., Vásquez, C., Ramón, J., y Llaque, A. (2023).Tax rules on wealth imbalance and the investigation of money laundering in Peru. Revista Criminalidad, 65(2), 159-170 https://doi.org/10.47741/17943108.490

Fredy Richard Llaque Sánchez PhD in Accounting and Finance University Professor Universidad de Lima Lima, Perú fllaque@ulima.edu.pe https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9809-5831

Catya Vásquez Tarazona PhD in Accounting and Finance University Professor Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos Lima, Perú cvasquezt@unmsm.edu.pe https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5955-7941

Jeri Ramón Ruffner PhD in Accounting University Professor Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos Lima, Perú jramonr@unmsm.edu.pe https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5951-6197

Alex Henry Llaque Sánchez PhD in Administrative Sciences University Professor Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú Lima, Perú allaque@pucp.edu.pe https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9230-1748

ABSTRACT

This study aims to evaluate the feasibility of using the tax methodology for determining unjustified increases in assets in money laundering cases heard in the courts. It also seeks to identify the errors made by the Tax Authority with the purpose of ascertaining whether these errors could hinder the successful application of the methodology in investigations of money laundering cases. In order to achieve these objectives, a mixed research methodology was conducted that included the analysis of rulings issued during the years 2020 and 2021 by the Peruvian Tax Court and sentences issued by the judiciary. This was complemented by semi-structured interviews with experts from the public sector, academia and accounting with relevant experience on the subject. The study found that there are some practical issues in the application of the methodology that can be overcome and that do not represent an insurmountable constraint. The study also found that the tax methodology allows for a more effective clarification of asset imbalances, and concludes that, once implementation errors have been overcome, the tax methodology can be feasibly employed to the benefit of money laundering investigations.

Keywords: Organised crime, corruption of officials, illicit enrichment, tax evasion, technical expertise (source: Latin American Criminal Policy Thesaurus - ILANUD).

RESUMEN

Esta investigación tiene como objetivos evaluar la factibilidad de utilizar la metodología tributaria de determinación de incrementos patrimoniales no justificados en la investigación de desbalances patrimoniales de casos de lavado de dinero ventilados en la vía jurisdiccional e identificar los errores que ha cometido la Administración Tributaria, a fin de establecer si estos representan problemas que pudieran dificultar la aplicación de la metodología a la investigación de casos de lavado de dinero. Con el propósito de lograr estos objetivos se condujo una investigación mixta que incluyó el análisis de las resoluciones emitidas durante los años 2020 y 2021 por el Tribunal Fiscal y sentencias emitidas por el poder judicial. Esto se complementó con entrevistas semiestructuradas a expertos del sector público, la academia y peritos contables con experiencia relevante sobre el tema. La investigación encontró que existen algunos empirismos aplicativos que pueden ser superados y que no representan ninguna restricción que no pueda ser gestionada. Se halló también que la metodología tributaria permite esclarecer de manera más efectiva los desbalances patrimoniales. La investigación concluye que, superados los errores de ejecución, es factible utilizar con ventaja la metodología tributaria en las investigaciones de lavado de dinero.

Palabras clave: Delincuencia organizada, corrupción de funcionarios, enriquecimiento ilícito, evasión de impuestos, peritaje técnico (fuente: Tesauro de política criminal latinoamericana - ILANUD).

RESUMO

O objetivo desta pesquisa é avaliar a viabilidade do uso da metodología tributária para determinar aumentos injustificados de patrimônio na investigação de desproporções patrimoniais em casos de lavagem de dinheiro julgados nos tribunais e identificar os erros cometidos pela Administração Tributária, a fim de estabelecer se estes representam problemas que poderiam dificultar a aplicação da metodologia na investigação de casos de lavagem de dinheiro. Para atingir esses objetivos, foi realizada uma pesquisa mista que incluiu a análise de decisões emitidas durante 2020 e 2021 pelo Tribunal Tributário e sentenças emitidas pelo judiciário. Isso foi complementado por entrevistas semiestruturadas com especialistas do setor público, acadêmicos e especialistas em contabilidade com experiência relevante no assunto. A pesquisa constatou que existem alguns empirismos de aplicação que podem ser superados e que não representam nenhuma restrição que não possa ser gerenciada. Também foi constatado que a metodología tributária permite um esclarecimento mais eficaz das desproporções patrimoniais. Na pesquisa, conclui-se que, uma vez superados os erros de implementação, é viável utilizar a metodologia tributária com vantagem nas investigações de lavagem de dinheiro.

Palavras-chave: Prisão; prisioneiro; estudo de caso (fonte: Tesauro da Unesco - Organização das Nações Unidas para a Educação, a Ciência e a Cultura), bairro, conexão, Chile, detentos (fonte: autor).

Introduction

When criminals endeavour to conceal the proceeds of crime from tax authorities, the police or the public prosecutor’s office, they face the complex problem of how to spend or invest the proceeds of their criminal activity without attracting the attention of state agencies. This problem is proportionally aggravated by the amount of investment or spending involved. The higher the spending or investment,1 the more quickly the offender will attract the attention of the authorities.

For this reason, criminals seek to “launder” the proceeds of their crimes before spending or investing them in the legal economy. OCDE (2019) notes that in order to be able to spend money openly, criminals will try to ensure that there is no direct link between the proceeds of crime and criminal activities. They may also try to prepare a plausible explanation of an apparently legal origin of the illicit money they possess. Criminals are often very creative and extremely careful in constructing these explanations. Their aim is to make it difficult to determine the illegal origin of funds, and to this end they use intermediaries and specialised professionals to construct and document the story. Important tools in efforts to uncover money laundering therefore include the use of proper investigative methodology, forensic auditing, and the support of effective whistleblowers, witnesses and collaborators.

The negative impact of money laundering on the legitimate economy has been widely documented, explaining that this activity distorts competition among businesses and entrepreneurs. Money laundering has also been shown to put the integrity of financial institutions at risk and that failure to combat it can create the perception that crime is rewarded, encouraging criminal behaviour.

In Latin America and the Caribbean there is consensus on the need to combat money laundering. If it is not curbed, as noted in the document produced by the Presidential Commission on Integrity (Comisión Presidencial de Integridad, 2016, p. 14), the state is left open to the risk of capture by criminal organisations that inject money from drug trafficking, illegal logging, illegal mining and smuggling, thus creating the conditions for the blurring of the fine line between corruption based on legitimately obtained money and that involving funds from the illegal economy.

Zevallos and Galdós (2003, pp. 14-15) consider that this problem is particularly serious given states’ weak capacity to control and supervise these types of illicit activities, especially given their underground and complex nature. According to Saldaña (2013, p. 175), the issue is even more complex, and the crime of money laundering or operations with resources of illicit origin is a problem on a global scale and a prominent hallmark of modern organised crime. Saldaña therefore argues that the issue cannot be dealt with in isolation, separated from other phenomena with which it is closely related. It is clear that money laundering qualifies as a problem of utmost seriousness, whose management requires a number of actions involving many different actors. For these actions to be successful, an ad hoc legal framework must be developed and optimised to adequately criminalise and punish money laundering and its predicate offences. Regulations that support the actions and powers of tax authorities, public prosecutor’s offices and national police forces must be optimised. The weaknesses of the entities involved must be addressed, as part of establishing a framework of collaboration and trust between them. This involves optimising, among other operations, the way in which intelligence is gathered, leads are acted on, evidence is collected and, where appropriate, how the asset imbalance is calculated.

The determination of asset imbalances in criminal proceedings in Peru

In Peruvian criminal law there are two regulations that criminalise offences related to money laundering committed by public servants or officials and other persons. The first refers to the illicit enrichment of public officials or servants and is contained in Article 401 of the Penal Code; this provision punishes any official who abuses their position to unlawfully amass wealth over their real capacity, which is judged by assessing their legitimate income.

The second reference is found in Legislative Decree 1106: Law against Money Laundering. In articles 1 and 2, this decree punishes anyone who carries out acts of conversion, transfer, concealment or possession of money, assets, goods, effects or proceeds of criminal or illicit origin, provided that they know its source or can be expected to have presumed its source.

In both cases, a first indication of possible unlawful activity is an obvious and unexplained increase in wealth. However, it is also necessary to verify that a person’s outgoings are greater than their available funds stemming from their legal income. The underlying logic is simple: if the wealth can be justified as deriving from legal sources, the resulting asset imbalance can be attributed to legal activity, or at least to sources of undeclared or untaxed income.

Aladino (2014, p. 22) recognises the complexity of investigations which determine the origin of goods or assets, and of inquiries into the history of the increase in wealth of the person under investigation. It is not a simple task to reach a conclusion as to whether or not assets are linked to criminal activities carried out by criminal organisations or by individuals acting on behalf of these as advisors or front men.2

Aladino also explains that behind these assets there is normally a set of complex, entangled or surreptitious operations whose purpose is to integrate money derived from an illicit activity into the formal economy, attempting to obfuscate any element or evidence linking the assets to said criminal activity.

In Peru, the Supreme Court of Justice on page 18 of the Plenary Agreement 03-2010/CJ-116 states that in order to convict for this crime, the Public Prosecutor’s Office, as the holder of the criminal case, must prove the crime took place. It also establishes that certain indications or circumstantial evidence must be taken into account, which include (a) an unusual increase in assets, (b) the dynamics of suspicious operations, (c) the insufficiency of licit businesses for a justification of the assets, (d) the explanation of acquisitions and the intended use for these, and (e) the direct or indirect link with persons or criminal activities that are related to money laundering.

The Plenary Agreement of 2010 also advises on signs of an “unusual increase in wealth”, such as the acquisition of goods without a justifying income to explain them, purchases of goods paid for by another person, or transactions regarding incompatible or inadequate goods.

The legal framework changed with Resolution of Nullity 1287-2018. It states that the criminal offence of money laundering does not require the complete demonstration of a specific criminal act to prove that money laundering has taken place, nor the identification of those responsible. It is sufficient to have reasonable certainty of the illicit origin of funds, that is, that they likely stem from an activity with sufficient potential for generating illicit profits (Corte Suprema, 2018).

In Peru, there are two main sources that produce records of asset imbalances. Firstly, the Public Prosecutor’s Office generates files of the investigations conducted by its prosecutors. Secondly, the Tax Authority (National Superintendence of Customs and Tax Administration; hereinafter SUNAT or Tax Authority) processes its own files on asset imbalances.

Net worth imbalance can only be determined through a process solely carried out by expert accountants or tax auditors with experience in the field. It also requires access to documents, books and accounting records, information from the parties and third parties involved in the assets and liabilities, and above all, the application of methods and procedures that allow for the clarification of the facts included in the evaluation. These experts are expected to objectively assess the evidence they are given or have collected on the origin of funds as well as the reasons behind the suspected crime. Specialists must assess the adequacy and reliability of the evidence in order to validate, confirm, clarify and explain the facts, using their expertise in law, economics, finance, accounting, auditing and taxation. It is clear, then, that for a proper investigation to take place, experts on the subject must be involved at every stage. Páucar Chappa (2013, pp. 70-71) confirms this, stating that the lack of experts on forensic accounting and financial auditing specialising in money laundering crimes is one of the determining factors for the success of investigations. This problem is manifested in two main ways. First, in the initial stages of an investigation, it can be difficult to understand the scope of the information to be submitted to experts, and crucial documentation can be omitted. Experts can play a vital role in providing guidance in this regard. Second, experts do not always obtain definitive conclusions to effectively balance the opinions provided by party-appointed experts. In other words, it is not the professional competence of the experts that impairs the quality of their opinions, rather, it is their lack updated specialised knowledge in comparison to some party-appointed experts who are recognized authorities in their field.

The results of the investigations are set out in the “expert report” or the “presumption of tax crime report”. These reports justify the evaluation process and the decision to accept or reject the evidence provided or gathered. They also evaluate the adequacy and reliability of the evidence that demonstrates the origin or amount of funds that were invested or spent.

The difference (imbalance) between the funds that the accused possesses (assets) or has spent (expenses) and their accredited income and liabilities is ascertained. This operation makes it possible to determine the “imbalance of assets” or the “unjustified increase in assets” which will be processed as a “money laundering offence” or as a “tax offence” as appropriate.

The literature review process of the present research comprised the analysis of a series of documents such as professional communications, theses and papers which study the problem of money laundering from different perspectives, including the robustness of the legal framework, the procedural aspects of conducting the investigation and the jurisdictional process, the possible infringements of the rights of those under investigation, and the assessment of evidence, among others.

However, there are very few Latin American studies that examine methods for establishing asset imbalance. This can be explained by the fact that economic- accounting determination is perceived as self-evident and particular to each case, given the technical, doctrinal and scientific basis supporting the determination of equity imbalances.

Without disregarding the above, one of the most controversial issues in cases heard in both administrative and jurisdictional proceedings is precisely the way in which the asset imbalance is established. In administrative proceedings, the issue is resolved relatively quickly, as the methodology and the process in general are supported by ad hoc tax regulations.

But the same is not true for cases deriving from the Public Prosecutor’s Office. The experts who produce these files do not follow uniform rules for the validation of the initial and final balances of the assets, the evaluation of the different transactions that have taken place in the period of analysis (movements, income, investments, yields, divestments, payments, renewals, expenses, consumption and losses, among others), nor for the evaluation of the adequacy and reliability of the supporting documents of the transactions that must be taken into account to establish the imbalances.

Although chartered accountants and tax auditors have the same objective and use the same methods and procedures to establish imbalances, they do not employ them in the same way. This is not necessarily wrong, but one cannot help but notice that it creates instability in the process of determining the asset imbalance.

The lack of uniformity in the proceedings generates discussion on issues that in some cases are insubstantial and can be used to delay the evaluation of the important issues. In extreme cases, these discussions are raised to generate confusion and doubts that, in order to better resolve the case, lead magistrates to request expert opinions that do not necessarily contribute to the discussion of the existence and amount of the imbalance and that, in extreme cases, could lead to the undue dismissal of a crime.

Tax rules for determining unjustified capital gains (IPNJ) in Peru

In the tax field, an unjustified capital gain (IPNJ) is an increase in wealth (either due to an increase in assets or a decrease in liabilities or a combination of both), for which the taxpayer cannot reliably prove the source of the increase. Peruvian tax regulations state that, if an imbalance is established in the assets of a natural person, the provisions of the Income Tax Law (LIR) and its Regulations (RLIR) will apply to this imbalance.

The first provision (1) of article 91 of the LIR grants SUNAT the authority to calculate tax liability using a presumed net income in the case of an increase in net worth whose origin cannot be justified.

This rule allows SUNAT to apply the presumed income when it detects any of the cases established in article 64 of the Tax Code (the provision that enables the application of the presumption), and provided that to proving that the imbalance is legitimate,3 the provision contained in article 52 of the LIR states that increases in assets cannot be justified by donations that have not been formalised in accordance with the relevant rules, profits from illegal activities, money from abroad whose origin is not substantiated, income whose receipt is not accredited that also fails to abide by the rules for such cases, and loans that do not comply with the requirements in force in the country.

The rules regarding the accreditation of loans are further developed in the provisions of article 60A of the RLIR. This rule states that, to justify the observed increase, loans must show a direct link between loaner and recipient, the source of funds must be identifiable, the traceability of the money in terms of its amount and type of currency must be substantiated, and the contracts that support the loan must bear certain dates and comply with the established formalities, among other conditions.

These regulations seek to justify the pre-existence of the transaction and the existence of the cash flow so that it can be associated with the established increase and used as evidence to support it.

Elsewhere in the tax regulations the provisions around the presumption of income are developed to make the application of presumed income more effective. In article 92 of the LIR, the tax legislator specifies that an increase in net worth will be established by considering external signs of wealth, variations in net worth, the acquisition and transfer of goods, investments, and deposits in accounts opened in national and foreign financial institutions, consumption and expenses, as well as the income and revenues verified by SUNAT.

This section explains the process to be followed in the determination of the increase and the elements to be analysed and clarified. With regard to the methods to be used, these have been regulated in article 60 of the RLIR. This provision includes a series of important definitions for the correct application of the presumption which are contained in paragraph a). They include definitions of equity, liabilities, initial and final equity, equity variation and consumption.

The tax legislator has defined these concepts to reduce discussion about them and to provide legal certainty to taxpayers. The definitions have a strong basis in accounting and therefore function correctly for the purposes of determining the imbalance. This rule also covers the issue of external signs of wealth. Article 60b of the RLIR provides that SUNAT may take into account the value of real estate acquired, owned and/or rented; assets used such as vehicles and boats; expenses that can be verified (social clubs, travel, education, etc.); investments in financial assets, intangible assets, works of art, etc.; in order to establish the increase in wealth. The rule states that these items must be valued using, as appropriate, the acquisition, production, or construction value, and failing these, the market value. The legislator has also laid out rules on how to deal with “unrealised gains” in paragraph c) of article 60 of the RLIR under the heading “Exclusions”. Even though these may eventually represent capital gains, as long as they remain unrealised (i.e., not disposable income) they cannot be counted as capital gains.

The LIR outlines two methods for the determination of unjustified capital gain: the balance plus consumption method and the method of acquisitions and disbursements. Both are discretionary and take into account the different circumstances that may be uncovered by the investigation. SUNAT may use either method at its discretion, however, the decision must not be made arbitrarily. The tax administration must evaluate the evidence and proof in its possession, or that it can obtain, in order to choose the method that will most effectively reveal and substantiate the increase. This is to ensure that the method selected is the most appropriate to the particularities under investigation. Section d) of article 60 of the RLIR explains each method and guidelines for their application to establish the capital gain. It specifies elements for analysis such as deposits in companies of the financial system, loans, disbursements made, among others. It also stipulates that in order to determine the increase, operations in which there is no change in net worth should be excluded, and includes specific examples, such as the transfer of money between accounts.

In paragraph d1) of the regulatory provision under the heading “Applicable exchange rates”, the legislator has developed a series of rules to deal with conversions of currencies which are not legal tender in Peru. While US dollars are frequently used for many transactions in Peru, and the most widely used foreign currency in the country, it is not the only one. Superintendencia de Banca, Seguros y Administradoras Privadas de Fondos de Pensiones (Superintendency of Banking, Insurance and Private Pension Fund Administrators) provides exchange rates for a wide range of currencies, but if the transaction, asset or liability is carried out or negotiated in a different currency, there are specific rules in place to handle the required currency conversions.

In subparagraph e) the legislator further develops the procedure for determining the capital increase, identifying exclusions that reflect the need to align cash flows with actual financial transactions and ensure that they have actually been used to make disbursements. It also provides rules on the suitability of certain documents to support the origin of assets and liabilities. It also indicates situations in which certain elements should not be taken into account, for example, when fictitious income and donations comply with the requirements established by the provisions.

The regulations establish that increases in income cannot be substantiated by funds that, although available to the tax debtor, were not used or collected. Positive balances of money in accounts of entities of the national or foreign financial system that were not withdrawn cannot be used for substantiation either. If these funds have not been used by the tax debtor, they obviously cannot be accepted as available for the operations under analysis.

Another important requirement of the RLIR is that lenders who are natural persons must enter into loan contracts with notarized signatures. Without a formalized contract, borrowers cannot use these loans to rebut a presumption of unjustified capital gains.

It should also be noted that these regulations state that the absence of tax returns submitted to the Tax Authority does not release the latter from verifying the accuracy of the taxpayer’s income or revenues. This serves as a safeguard and does not simplify the evidence gathering work of SUNAT, while also acknowledging that administrative sanctions may be imposed if applicable. Additionally, it is important to emphasise that the legislator has provided for the rejection of a source of unrealized income and of a series of situations that were commented on above when discussing article 52 of the LIR. This avoids scrutiny of the amount of unjustified capital gain in situations where questioning of a source of income is unnecessary as it does not correspond to flows of funds effectively credited.

This is not the only problem that the tax legislator has addressed in the regulations. Another important issue is dealing with transactions where the market value is not appropriate. This is the case in situations where the value of a transaction is considered to be overvalued or undervalued. In paragraph f), the legislator has empowered the tax authority to adjust these values. Under the heading Market value, it states: “In the case of goods whose assigned value is in doubt, SUNAT may adjust them to market value”. It should be noted that this is not an arbitrary adjustment, since the provisions of article 32 of the LIR must be followed, complemented by the provisions of article 19 of the RLIR. Abundant case law has delimited the situations in which this adjustment can be made.

Finally, after the Tax Authority has completed the preceding step, it can then establish the presumed net income, the “net worth imbalance”, which is subject to taxation for income tax purposes. In the case of the income of natural persons, in subsection g) under the heading “Presumed net income”, the legislator stipulates that “the presumed net income shall encompass any unjustified increase in assets, which shall be added to the individual’s net income deriving from employment”. This regulation is necessary for determining income tax, in accordance with the method of determining income that is currently applied in these cases in Peru.

Methods of proof and assessment of evidence in taxation, criminal and civil proceedings

Lopo Martínez (2021, pp. 25-26) emphasises that, in the field of taxation, evidence (normally accounting evidence) is important in most cases for the effective application of taxes and for providing legal certainty to the procedure. He explains that evidence obtained in tax proceedings does not only affect the fields of civil or criminal law, it can also impact all scientific fields making up human knowledge. In the modern scientific paradigm, with the appropriate evidence, it is possible prove an “almost absolute” truth in various fields of knowledge, eliminating uncertainty about a disputed fact without needing to establish strict certainty. In a court of law, this allows the judge to form a belief about a fact and make a decision.

Cases initially brought before the tax authority may subsequently be escalated to be heard in civil or criminal courts. In these scenarios, the accounting evidence obtained in tax proceedings is admitted. In Peru, both the Code of Civil Procedure (CPC) and the Code of Criminal Procedure (CPP) have included various articles that guide legal operators on the proper collection and evaluation of evidence. In the CPC, article 188 and subsequent articles cover topics such as the purpose of evidence, the suitability of different types of evidence, the lawful methods of evidence, and the evaluation of evidence. Article 157 and subsequent articles of the Code of Criminal Procedure cover the same subject in the context of criminal proceedings.

Important information is also contained in the provisions of article 192 of the CPC, which identifies the following standard types of evidence: 1. Statement of the defendant, 2. Statements from witnesses, 3. Documentary evidence, 4. Expert statements, and 5. Judicial inspection. For criminal cases, in numeral 1) of article 157(1) of the CCP, it states: “The facts subject to evidential scrutiny may be substantiated by any methods of proof permitted by law. In exceptional cases, other methods of evidence may be used, provided that they do not infringe the rights and guarantees of the individual, nor the legally recognized powers of the parties to the proceedings. The manner in which these alternative types of evidence are incorporated shall be adapted to resemble the most appropriate among the officially recognised methods, as far as is possible.”

Additionally, numeral 2) states: “In criminal proceedings, the evidentiary constraints established by civil law shall not be taken into account, except those that refer to the civil or citizenship status of persons”. As can be seen, the rules around evidence are essentially the same in both codes, although criminal law takes a much broader stance.

For Lopo Martínez (2021, p. 374), the evaluation of accounting evidence consists of making reasonable judgements about the accounting facts that are important for solving the case, so that they can be established as proven or demonstrable. Such judgements must be informed by the rules of formal logic, and adhere to the maxims of common experience, to ensure that they correspond to the facts of real life. They must also be formed on the basis of evidence, taking into account the accounting evidence provided.

In Peruvian law, the assessment of evidence for the purposes of civil law is set out in article 197 of the CPC, which states: “All methods of evidence are assessed by the judge as a whole, using their reasoned assessment”. For criminal law purposes, article 158 of the CPP provides the following: “1. In the evaluation of the evidence, the judge must observe the rules of logic, science and the maxims of experience, and shall explain the results obtained and the criteria adopted”. Paragraphs 2) and 3) of the aforementioned article deal with the treatment of witnesses and the use of circumstantial evidence. While the CPP develops this subject in much broader, protective and demanding terms, its rules around the treatment of evidence are similar to those of the civil code. This is the understanding of the Plenary Jurisdictional Cassation Court of the Permanent and Transitory Criminal Chambers, Plenary Cassation Court Judgement 1-2017/CIJ-433, which considers that “conviction requires proof beyond reasonable doubt”.

This raises the question of how judges define and apply the standards of “reasonable certainty” and “beyond reasonable doubt”. The initial impression is that the requirements of criminal law are appropriately much more stringent, and that the evidence and evaluation process of administrative courts and civil judges is insufficient for the purposes of criminal justice. However, this assumption of insufficiency is not always correct; on occasions, the administrative standard produces files in which the evidence is so strong that the assessment process allows the judge, whether in a civil or criminal context, to meet the requisite standards for a ruling. Civil judges in Peru seeking “reasonable certainty” have managed to find it in almost all of the cases they have resolved since 2014, which therefore confirms that the standard of evidence for administrative cases is sufficient.4

Very few IPNJ case files first dealt with by the tax authority as a tax offence have been heard in the criminal justice system.5 However, even in these very few cases, the judges managed to meet the criminal standard of “beyond reasonable doubt” and upheld the ruling that had been dictated under the Tax Authority.

Methodology

The present research aims to achieve two objectives: (a) to identify problems that have arisen when applying tax presumption to the IPNJ determination process, and

(b) to explore the feasibility of the IPNJ determination methods regulated in the LIR and the RLIR as reference methodology in the quantification of asset imbalances for money laundering investigations conducted in Peru.

A non-experimental study employing a qualitative approach was proposed to achieve these objectives.The study also applied documentary, exploratory and descriptive research methods.

To achieve the first research objective, the resolutions of the Tax Court (RTF) issued between 1 January 2020 and 31 July 2021 were used as a secondary source. The rulings were located by searching the Tax Court’s website,6 using the phrase “incremento patrimonial no justificado” as a search term. The search yielded 67 RTFs. These results were filtered to ensure that the ruling referred to the subject of the present investigation, which left a total of 59 relevant rulings.

Given the number of cases, the decision was made to work with all of the relevant RTFs as a complete set, using a documentary analysis technique. For this, a data collection form was developed in which relevant information would be gathered for the analysis of problems arising during the application of the presumed figures.

To complement this information, cases of IPNJ heard in court were also included in the study. These cases were located by searching the National Jurisprudence Systematization database7 with the key words “incremento patrimonial” (growth in assets). The search yielded 40 rulings, of which 4 were discarded as they were not relevant to the topic under study. Given the number of judgments, it was preferred to work with the whole set rather than with a sample.

In order to achieve the second objective, semi- structured in-depth interviews were conducted with nine experts on the subject; an interview guide was prepared for this purpose. The experts interviewed were accountants or lawyers with more than ten years of experience in cases in administrative or criminal courts in which asset imbalances were discussed. The distribution of experts was as follows: tax auditors (3), chartered accountants (3), academics with experience in providing independent advice on asset imbalance cases (3).

The interviews contained 14 questions. The first seven were aimed at establishing whether the interviewee’s opinion could qualify as an expert opinion in this study and whether they were familiar with administrative and/ or jurisdictional cases relevant to the research. The following seven were open questions and were aimed at gathering expert opinion regarding the application of the tax methodology, its overall robustness and the possibility of its use for the purpose of determining unjustified increases for criminal cases. The data collection form and the interview guide were validated by five judges: two lawyers, two accountants and one methodologist. The judges made comments about the form and agreed to award an Aiken V score of 0.95.

Results

Problems in the application of the LEI presumption in 2020 and 2021

To justify the decision to lodge a claim and subsequent appeal to the Fiscal Tribunal, administrators generally provided the following arguments:

a. That the grounds required for the tax authority to apply the presumptive base determination had not been met, or that errors had occurred in the determination of the presumptive base, or that the presumption had been incorrectly calculated.

b. That the disclaimers presented during the audit process had not been adequately assessed.

c. That the methodology employed had not been applied in accordance with the provisions of the LIR and the RLIR.

d. Procedural errors (such as incorrect notification or insufficient deadlines, etc.) had been committed during the processing of the audit that limited their right of defence.

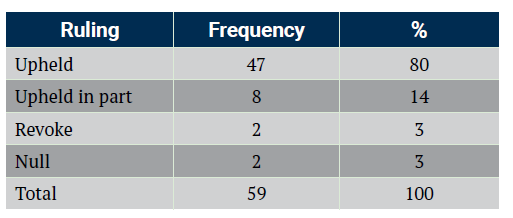

For each appeal, following the evaluation of the files, the Tax Court issued a ruling. The outcome of the appeals is shown in Table 1.

Tabla 1. Rulings of the Tax Court on appeals concerning unsubstantiated capital gains.

As can be seen in Table 1, of the 59 cases decided by the Tax Court, 47 were upheld in full (80 %) and 8 were upheld in part (14 %). In total, 94 % of the cases were favourable to the tax authority’s claims, even in the case of those upheld in part.

The data show that the Tax Court considered the Tax Authority’s assessment process to be correct and considered that the taxpayers’ arguments based on fact and law were not sufficient to invalidate the assessment made.

Despite the upholding of a high percentage of the files submitted by the Tax Authority, the result is not unanimous. To identify specific errors, it is necessary to analyse the files in which the Tax Court decided to “nullify” or “revoke” the original ruling, and to analyse in more detail the cases which were “upheld in part”.

Table 1 shows that there are 12 cases with rulings that went against the claims made by the Tax Authority. In half of these cases, the court considered, contrary to SUNAT’s criteria, that some income or deposits had been adequately substantiated and ordered the Tax Authority to reassess the debt accordingly. It is important to note that the taxpayer may in some cases submit additional documentation after the closure of the audit. When the court assesses this additional material, it may impact the outcome of the case in this way.

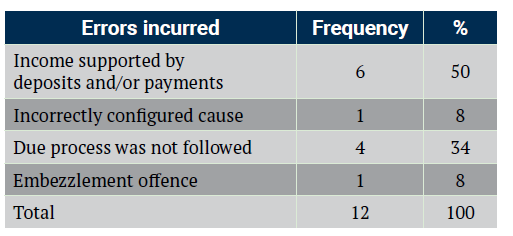

In one case the Tax Authority was found to have wrongly identified the cause of asset imbalance, in four cases the procedure for processing the tax audit presented a flaw that SUNAT was ordered to rectify, and in one case the increase could be linked to an investigation of embezzlement. A summary of these results is shown in Table 2.

Tabla 2. Errors in the application of the presumption.

Additionally, an analysis was carried out of the judgments of the civil courts on cases of IPNJ initiated by the Tax Authority.8 In 33 of the 36 cases, the judges upheld the actions of the Tax Authority. Two cases were overturned, and one case was declared null and void. The importance of this analysis is that it has established that civil judges have met the standard required, having been provided with evidence that has allowed them to reach reasonable certainty as to the existence of an IPNJ.

Feasibility of using the LIR’s IPNJ determination methodology to establish asset imbalances in money laundering cases

The tax auditors interviewed assert that the methodology they follow is robust and this is confirmed by the high level at which their case files are validated both in the Tax Court and in the Judiciary. They also state that during discussions among experts they have had no major problems in supporting the methodology and consequently defending and substantiating the file in the context of observations raised by the accounting experts, both those appointed by the court and by the party.

In reference to the methodology used and evidence provided, tax auditors state that they do not normally have problems in establishing the initial assets of individuals or groups of individuals. In general, in order to validate income, expenditures and assets, the Tax Authority consults its different databases and when appropriate, requests access to public registries, notaries, justices of the peace, the financial system, client and supplier information, among other sources. Additionally, they emphasize that the Tax Authority has significant capabilities for obtaining information. These include its internal resources which enable decentralised audit areas to request or directly obtain information at their headquarters in order to contribute to an investigation carried out at another location. They can also request banking and stock market confidentiality to be lifted and seek international administrative assistance from other tax authorities in order to obtain information from abroad. All of these resources allows the Tax Authority to validate both the initial and final balances and to establish the IPNJ by calculating the difference between the increase and the substantiated amounts.

The majority of the accounting experts and representatives of academia interviewed point to the lack of a specific regulation and uniform procedure for the determination of asset imbalances as the main causes leading judges to order retrials when presented with criticism from the defence team, which is often unsubstantiated. Judges are duty bound to accept these observations and order further proceedings in order to convince the court of the existence of asset imbalances. According to those interviewed, the defence team’s strategy is to cast reasonable doubt of the imbalance and its calculation in the judge’s mind. Their aim is to prompt the judge to order retrial proceedings to delay the process or to secure a ruling in their favour and the dismissal of the claims made by the Public Prosecutor’s Office.

The expert accountants consider that the methodology used by SUNAT to establish the IPNJ, especially in cases heard at the jurisdictional level in which they have been involved, tends to be received more favourably by magistrates. This does not mean that the methodology is not scrutinised, rather, after discussions with experts, judge usually accepts the assertion that an imbalance exists.

With regard to the challenges that are usually made to tax case files, experts highlight four key areas: the existence of the enabling cause, the acceptance and rejection of evidence, the process of determining the IPNJ and finally procedural aspects that may represent a violation of the taxpayers’ right of defence. They assert that these four areas are also the most controversial and the basis for challenges made for files produced outside the Tax Authority. They also commented that the scope of the evidentiary work is also an important problem and acknowledge that the Tax Authority has better capabilities for building evidence than other entities.

They indicate that, probably due to the specificness of tax matters, discussions concerning the determination of the IPNJ established by SUNAT usually focus on the evaluation of evidence, rather than the methodology itself. In their experience, the discussion on the relevance of the evidence is often employed as a strategy to prolong the legal proceedings. This is because, typically, given the rigorous evidentiary procedures conducted by SUNAT, coupled with its authority to gather evidence and proof, enable it to build a stronger case and conviction.

With respect to the monetary determination of the IPNJ, tax auditors point out that they do not take into account data that cannot be validated. Despite the fact that the Peruvian economy has high levels of informality, auditors do not incorporate transactions that have not been declared to SUNAT or whose origin has not been validated by SUNAT. During the audits carried out by this entity over the years, expenses for living costs or travel expenses within the country or abroad are not typically “presumed” or considered. Only those expenses that can be identified and duly quantified and valued are incorporated into the calculation. The explanation for this is simple: even if a formal or informal legal activity can explain the funds responsible for the increase, if it has not been declared to SUNAT and has not been taxed (when applicable), these funds should be subject to taxation. Therefore they should not be considered when determining the IPNJ and should not, by themselves, serve as evidence of tax evasion.

The chartered accountants and experts from academia interviewed explained that it is normal practice for reports produced outside the Tax Authority to use economic and financial assessment methodologies that include estimates of investments and returns. Estimates of living costs or travel expenses are included in some cases. They recognise that this consists of a “presumption” but that it is justified, arguing that a presumption is necessary to best approximate the funds available to and spent by the accused, especially in cases where the accused does not provide evidence or where the evidence provided is dubious. It is also widely accepted that this practice implicitly recognises that there is money available that has derived from informal activities which, although not declared to the tax authority, should be considered in the calculation, as they do not necessarily qualify as criminal in origin. Most of the accountants and experts from academia recognise that the methodology used by SUNAT is more robust than those employed by other entities and consider that its use in money laundering cases is appropriate. However, they communicated a concern that, the strict structure of the methodology may represent a limitation that, in some cases, could prevent an imbalance from being established. Nonetheless, most of these experts acknowledged that this limitation is more of a theoretical restriction than a real one, opining that while the tax procedure is tightly structured, this does not represent an insurmountable restriction and is flexible enough to be adapted to complex situations without being distorted.

In sum, the interviewees consider that there are more benefits than disadvantages in employing the methodology used by SUNAT to establish IPNJ as a mandatory reference methodology in the determination of asset imbalances related to money laundering. They also consider that the weaknesses identified in SUNAT’s performance in the cases decided by the Tax Court can be overcome and a more robust procedure and methodology to be established for criminal purposes.

Discussion

As discussed in the analysis of the IPNJ presumption contained in the LIR and in the RLIR, the methodology and the procedure for determining the IPNJ in the sphere of tax administration serves as a guarantee of taxpayers’ rights. These procedures oblige the Tax Authority to carry out a thorough and rigorous process in their task of evidence building. The legislator has not simplified the work of the Tax Authority, as could be said to be the case with other presumptions. Here, the legislator has instead focused on gathering the available evidence by applying the rules of accounting, finance, economics, auditing and general legislation in a technical, objective and impartial manner. These elements together make up a determination procedure that enables the increase to be established in an objective manner.

This study also examined cases of IPNJ resolved in administrative and jurisdictional courts over recent years. Their analysis shows that the legal framework supporting the presumption is robust and that, although there are some ongoing problems in its application, these mostly pertain to practical issues of application that must be overcome in order to reduce litigation, expedite the litigation process and provide greater legal certainty.

Based on this research, we think that a plenary agreement could guide judges and the Public Prosecutor’s Office in employing in court the practices followed by the Tax Authority. This would contribute to overcoming the weaknesses detected in the files processed by the Public Prosecutor’s Office. We believe that such an agreement could guide judges while also allowing for flexibility, and thus improve the administration of criminal justice in money laundering cases.

This study paves the way for more specific research to improve understanding of the subject. Among the issues requiring further study in Peru is the widespread adoption of a full chamber agreement and its insertion into the legal system at the appropriate legal level.

Conflict of interest

There was no conflict of interest among the authors of this academic research. We declare that we have no financial or personal relationships that could influence the interpretation and publication of the results obtained. We also confirm that we have complied with ethical standards and scientific integrity at all times, in accordance with the guidelines established by the academic community and those dictated by this journal.

Footnotes

1. While smurfing can be considered an exception to this statement, this technique is only effective in the short term, as a robust detection system will be able to identify it sooner or later.

2. Front men may or may not be aware that they are involved in an illegal activity, but even in cases where they are not aware, in the Peruvian legal system, they are considered to have committed a crime because “they should have presumed that the origin is unlawful”.

3. Over time, abundant jurisprudential precedents have delimited the scope of the methods of substantiation and their assessment. Thus, there are now a series of resolutions of the Tax Court (RTF): 09220- 4-2005, 03616-2-2008, 0366-5-2007, 00654-4-2010, 01479-10-2013, 07512-8-2012, 02186-2-2015, 02734-4-2015, 02931-3-2015, 02216- 1-2015, 03600-1-2005, 09282-3-2015, 1129-8-2015, 02308-4-2016, 01601-2-2016, 10203-1-2016, 01121-8-2016, 01309-2-2017, 08669- 2-2017, 06059-1-2017. Although the precedents are administrative, it is nevertheless clear that they are appropriate for the purpose of properly delimiting and shaping the process of determining increases in wealth.

4. A consultation carried out on the Judicial Power’s databases found that 36 cases have been resolved between 2014 and the date of the consultation.

5. Files 04382-2007-PA/TC and 04985-2007-PA/TC

6. https://apps5.mineco.gob.pe/transparencia/Navegador/default.aspx

7. https://jurisprudencia.pj.gob.pe/jurisprudenciaweb/faces/page/inicio.xhtml

8. Of the 33 judgments, the following cases uphold the actions taken in the administrative instance: 18861-2016, 5112-2017, 5511-2017, 15115-2017, 10748-2014, 11394-2014, 5850-2015-0, 3071-2014, 7759-2018-0, 6955-2019, 664-2018, 7359-2018, 3757-2019, 12951- 2019, 7800-2021-0, 7187-2015, 9210-2016, 18861-2016, 5112-2017, 5511-2017, 15115-2017; and in cassation: 9748-2017, 23910-2021, 1056-2020, 3931-2017, 12475-2019, 431-2016, 18100-2015, 2461- 2017, 26863-2019, 18084-2016, 18968-2016, 19673-2019, 2461-2017. There have been three cases in which the original ruling was revoked: exp. 02192-2016-0-1801-JR-CA-18 and exp. 05181-2017-0-1801-JR- CA-22. One case was pronounced null: cassation judgement 9561- 2014, Lima.

References

Aladino, G. V. (2014). El delito de lavado de activos, criterios sustantivos y procesales. Análisis del Decreto Legislativo n.° 1106 [The offence of money laundering, substantive and procedural criteria. Analysis of Legislative Decree n.° 1106]. Instituto Pacífico – Actualidad Penal.

Corte Suprema. (2018). Resolución de Nulidad n.° 1287- 2018, Sala Penal Permanente Nacional de la Corte Suprema. https://shorturl.at/qySU9

Comisión Presidencial de Integridad. (2016). Informe de la Comisión Presidencial de Integridad. Detener la corrupción, la gran batalla de este tiempo [Report of the Presidential Integrity Commission. Stopping corruption, the great battle of our time]. https://shorturl.at/LXZ13

Instituto Latinoamericano de las Naciones Unidas para la Prevencion del Delito y Tratamiento del Delincuente, ILANUD. (1988). Tesauro de Política Criminal Latinoamericana.

Lopo Martínez, A. (2021). Prueba contable en el derecho tributario [Accounting evidence in tax law]. Aranzadi/ Civitas. https://shre.ink/9zaJ

OCDE. (2019). Lavado de activos y financiación del terrorismo: manual para inspectores y auditores fiscales [Money laundering and terrorist financing: A handbook for inspectors and auditors prosecutors]. OCDE.

Paucar Chappa, M. E. (2013). La Investigación del delito de Lavado de Activos. Tipologías y Jurisprudencia. Ara Editores, Lima.

Saldaña, R. (2013). La autonomía del lavado de activos [Autonomy of money laundering]. Gaceta Jurídica.

Zevallos, T., y Galdós, M. (2003). Elementos para el análisis de las capacidades de control del lavado de activos [Elements for the analysis of money laundering control capabilities]. In Centro Latinoamericano de Administración para el Desarrollo, VIII Congreso Internacional del CLAD sobre la Reforma del Estado y de la Administración Pública (pp. 28-31). CLAD.