Resolving execution of judgment in Indonesia investment fraud case to ensure asset recovery for victims

Resolución de la ejecución de sentencia en un caso de fraude de inversiones en Indonesia para garantizar la recuperación de los activos de las víctimas

Resolução da execução da sentença no caso de fraude de investimento na Indonésia para garantir a recuperação de ativos para as vítimas

- Date received: 2023/11/23

- Evaluation date: 2024/06/11

- Date approved: 2024/07/18

To reference this article / Para citar este artículo / Para citar este artigo: Resolving execution of judgment in Indonesia investment fraud case to ensure asset recovery for victims. Revista Criminalidad, 66(3), 81-95. https://doi.org/10.47741/17943108.663

Kuat Puji Prayitno

Universitas Jenderal Soedirman

Purwokerto, Indonesia

kuat.prayitno@unsoed.ac.id

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0481-2439

Dwiki Oktobrian

Universitas Jenderal Soedirman

Purwokerto, Indonesia

dwiki.oktrobrian@unsoed.ac.id

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6772-1409

Tedi Sudrajat

Universitas Jenderal Soedirman

Purwokerto, Indonesia

tedi.sudrajat@unsoed.ac.id

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2734-2820

Sri Wahyu Handayani

Universitas Jenderal Soedirman

Purwokerto, Indonesia

sri.handayani@unsoed.ac.id

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7507-9014

Abstract

In response to investment fraud, the criminal justice system should place the victim at the centre, considering their financial loss. Indonesia has responded by establishing asset recovery for victims; however, there are signs of stagnation in its execution. This study aims to explain the causes and solutions to such stagnation so that victims can benefit from the justice system. This study uses a case study and statutory approach to analyse the operation of execution provisions in asset recovery. A case in the city of Cirebon (West Java Province) was selected because the execution has not been completed despite having been initiated since 2017 to prevent similar failures, as Indonesian courts have now tended to favour asset recovery. Primary data were obtained from interviews with officers directly involved in the execution of the case, supplemented by secondary data obtained through regulatory analysis and a literature study. This article discloses the serious problems in asset liquidation faced by executing agencies, as perpetrators have already completed their prison terms, even though victims have yet to receive their entitlements. Prolonged stagnation has led to the perception that access to asset recovery is non-executable. This study offers a solution towards synchronising regulations and empowering the resources of the criminal justice system more optimally.

Keywords:

Asset recovery; execution; investment fraud

Resumen

En respuesta al fraude de inversiones, el sistema de justicia penal debe situar a la víctima en el centro, teniendo en cuenta su pérdida financiera. Indonesia ha respondido estableciendo la recuperación de activos para las víctimas; sin embargo, hay signos de estancamiento en su ejecución. Este estudio pretende explicar las causas y soluciones de dicho estancamiento para que las víctimas puedan beneficiarse del sistema judicial. Este estudio utiliza un enfoque casuístico y estatutario para analizar el funcionamiento de las disposiciones de ejecución en materia de recuperación de activos. Se seleccionó un caso en la ciudad de Cirebon (provincia de Java Occidental) porque la ejecución no se ha completado a pesar de haberse iniciado desde 2017 para evitar fallos similares, ya que los tribunales indonesios tienden ahora a favorecer la recuperación de activos. Los datos primarios se obtuvieron a partir de entrevistas con funcionarios directamente implicados en la ejecución del caso, complementados con datos secundarios obtenidos mediante análisis normativo y un estudio bibliográfico. Este artículo revela los graves problemas en la liquidación de activos a los que se enfrentan los organismos de ejecución, ya que los autores han cumplido sus penas de prisión, aunque las víctimas aún no han recibido sus derechos. El estancamiento prolongado ha llevado a la percepción de que el acceso a la recuperación de activos no es ejecutable. Este estudio ofrece una solución para sincronizar las normativas y potenciar de forma más óptima los recursos del sistema de justicia penal.

Palabras claves:

Recuperación de activos; ejecución; fraude en inversiones

Resumo

Em resposta à fraude de investimento, o sistema de justiça criminal deve colocar a vítima no centro, considerando sua perda financeira. A Indonésia respondeu estabelecendo a recuperação de ativos para as vítimas; no entanto, há sinais de estagnação em sua execução. Este estudo tem como objetivo explicar as causas e soluções para essa estagnação, de modo que as vítimas possam se beneficiar do sistema judiciário. Este estudo utiliza uma abordagem de caso e estatutária para analisar o funcionamento das disposições de execução na recuperação de ativos. Um caso na cidade de Cirebon (Província de Java Ocidental) foi selecionado porque a execução não foi concluída, apesar de ter sido iniciada desde 2017 para evitar falhas semelhantes, já que os tribunais indonésios agora tendem a favorecer a recuperação de ativos. Os dados primários foram obtidos por meio de entrevistas com funcionários diretamente envolvidos na execução do caso, complementados por dados secundários obtidos por meio de análise regulatória e um estudo da literatura. Este artigo revela os sérios problemas de liquidação de ativos enfrentados pelos órgãos de execução, uma vez que os perpetradores cumpriram suas penas de prisão, embora as vítimas ainda não tenham recebido seus direitos. A estagnação prolongada levou à percepção de que o acesso à recuperação de ativos não é executável. Este estudo oferece uma solução para sincronizar as regulamentações e capacitar os recursos do sistema de justiça criminal de forma mais otimizada.

Palavras-chave:

Recuperação de ativos; execução; fraude em investimentos

Introduction

The prosecution of investment fraud cases in Indonesia has increasingly incorporated the aspect of asset recovery for victims, given the magnitude of victimisation. Victims have long been neglected within the criminal justice system and are considered a minor concern in the contemporary codification of criminal procedural law (Novokmet, 2016). Starting from the 1960s and 1970s, when awareness of the marginalisation of victims emerged, shifts have occurred, acknowledging the emotional aspects of victims, such as their feelings and frustrations as part of the criminal justice system (Green et al., 2020). Notable cases include the First Travel case in 2023, the Binary Option case in 2022 involving Binomo (Tangerang) and Quotex (Bandung), the Cakrabuana Sukses Indonesia (CSI) case in 2017 (Cirebon), and the Cipaganti case in 2015 (Bandung). The First Travel case recently concluded the examination process that began in 2018, while the Binary Option case is still under review by the Supreme Court. In the CSI case, execution has been ongoing since 2017 but remains unresolved, whereas the Cipaganti case was resolved through civil proceedings, with the victims initiating a bankruptcy scheme. In the CSI case, 3 868 victims are still awaiting the completion of the liquidation process involving 59 properties at the State Auction Office. Based on these circumstances, asset recovery has been accommodated by the courts; however, the execution aspect has not been adequately considered.

Fraud entails the intentional manipulation of facts to deceive individuals into surrendering valuable assets or legal entitlements (Akers & Gissel, 2006). It encompasses the dissemination of false information, involving either the deliberate suppression of vital details or the provision of misleading statements, all aimed at obtaining gains that would be unattainable without resorting to deceit (Doig, 2013). One manifestation of fraud is investment fraud, which involves dubious investment schemes orchestrated by unregistered entities. These entities lure investors into allocating funds, only for the investors to suffer financial losses in the end (Deb & Sengupta, 2020). Investment fraud represents an intricate and sophisticated form of organised crime that targets both seasoned and inexperienced investors. It entices individuals, including non-opportunistic investors, to partake in investment opportunities associated with fictitious instruments or worthless securities (Lacey et al., 2020). Considering these points, investment fraud epitomises a deceptive practice that demands calculated execution by perpetrators and a lack of vigilance on the part of victims, thereby ensnaring them in detrimental investment ventures.

Contrary to “implementation” or “effect,” “execution” refers to the legally binding nature of court rulings (Lambert-Abdelgawad, 2002). The execution of a court judgment refers to the implementation of a final and unchangeable decision, wherein the losing party (the convicted) is compelled to comply through the use of government authority if they fail to do so voluntarily (Hamzah, 2008). In brief, the execution is defined as the manner in which criminal sanctions must be carried out out (Arief, 2008). Courts in Indonesia tend to let their judgments speak for themselves. This practice is due to the design of the criminal justice system within the Indonesian Criminal Procedure Code (KUHAP), which is neither integrated nor comprehensive. This situation renders court decisions non-executable, thereby leading to a rejection of the judiciary (De Londras & Dzehtsiarou, 2017). This lack of integration stems from the absence of adequate regulations and policies, which assign judges the duty to supervise the execution of their rulings (Timoera, 2018). In the end, this system becomes incomplete by neglecting execution as the final stage of the process, even though a comprehensive criminal justice system necessitates four stages: investigation, prosecution, adjudication, and execution.

Asset recovery encompasses a series of activities encompassing the tracing, securing, preservation, expropriation, and restitution of assets linked to criminal offenses or violations, ultimately restoring them to the state or to their rightful owners. Asset recovery emerged as a global response to combat corruption and money laundering in 2007 through “The Stolen Asset Recovery” (StAR) initiative, subsequently incorporated as Chapter 5 of the United Nations Convention Against Corruption (UNCAC). The scope of asset recovery has expanded beyond corruption-related offenses and has assumed a prominent position in national and international law enforcement policy agendas (Chistyakova et al., 2021). Various studies have examined the impediments to successful asset recovery, revealing certain prevailing trends. Firstly, there are divergent perspectives between law enforcement agencies and judges regarding the burden of proof for predicate crimes and the potential efficacy of civil proceedings (Dewi et al., 2018; Kaniki, 2021; Sittlington & Harvey, 2018). Secondly, there is an absence of a centralised asset recovery management centre responsible for overseeing the process (Suud, 2020; Tasdikin & Wahyudi, 2022; Zolkaflil et al., 2023). Thirdly, the implementation of the non-conviction-based principle in confiscation aims to reduce obstacles in asset recovery, but it has the potential to castrate the suspect’s human rights (Cassella, 2019; Fauzia & Hamdani, 2022; Junqueira, 2020). In this context, the present study focuses on the gap between court judgments and the execution thereof. This gap primarily stems from a fundamental internal factor, namely national criminal law policies. This article provides a unique exploration of the aspects that have been overlooked within national legal policies, resulting in execution stagnation.

This study aims to contribute to the existing literature on the execution of asset recovery for victims of investment fraud cases, ensuring that the rights of victims of these crimes can be accessed after the court has made its decision. The importance of asset seizure in financial predatory crime cases stems from two key justifications: providing compensation to victims by using recoverable funds and reducing or eliminating the perpetrators’ opportunity to enjoy the fruits of their greed (Brun et al., 2021). From a restorative justice perspective, the ill-gotten gains of offenders should rightfully be seized and returned to the victims (Thomas et al., 1995). Based on these considerations, three questions are formulated to analyse the aforementioned issues. Firstly, how can restitution arrangements ensure effective asset recovery? Secondly, what is the state’s financial support for subsidising asset recovery activities? Thirdly, how does the court implement a monitoring and evaluation scheme for the executing agency? These questions serve as the focal point guiding the entire discussion in this article while also elucidating the underlying reasons for the phenomenon of asset recovery execution stagnation in Indonesia. Based on the trend of Indonesian court decisions that have provided asset recovery, as in the first paragraph, it is appropriate for the state to bestow more optimal resources to ensure that asset recovery can be carried out completely.

This study focuses on the CSI case, based on the Sumber Court Decision No. 193/Pid.B/2017/PN Sbr; CSI was formed in December 2011 as a trading company. In 2014, CSI changed its legal form from a company to a cooperative and marketed the investment product “sharia-based gold gardening” with a profit scheme of 5 % every month or 60 % a year. During the three years of operation (2017), 979 investors were collected based on company documents; however, according to witnesses, there were 2 619 investors. The police and prosecutors were only able to find IDR 2 000 000 000 and 59 properties as objects of confiscation from the investment value of IDR 285 070 028 461.03. The head of CSI was sentenced to seven years of imprisonment and confiscation of assets for violating Article 59 of the Sharia Banking Law, “unlawfully collecting public funds” (Pengadilan Negeri Sumber, 2017).

This article makes a contribution that focuses on the issue of the potential for victims to receive tangible benefits from asset recovery efforts. Several focuses of previous articles include integrating asset recovery within restorative justice (Ali, 2020), tracing assets that can be confiscated (Wibowo, 2023), freezing assets (Ramos & Pereira Coelho, 2023), and constructing asset recovery as a part of the punishment (Pavlidis, 2023). These various contributions demonstrate that the assurance of victims receiving benefits from asset recovery has not yet become a focus of the international community. This article highlights this issue as a contribution proposed for international discourse. Referring to the evolving practices in the European Union, several examples of asset recovery regulations can be highlighted. First, the fight against corruption can be optimised in efficiency by strengthening asset recovery (Pavlidis, 2023). Second, asset recovery for crimes beyond corruption, such as fraud, is conducted by blocking assets spanning multiple jurisdictions and facilitating the involvement of victims in the asset recovery procedure (Ramos & Pereira Coelho, 2023). Third, the policy framework of forfeiture and confiscation in asset recovery must consider protections for those affected by these policies (Sakellaraki, 2022). This article offers a contribution to an international discourse that has been scarcely addressed concerning the assurance for victims to benefit from asset recovery based on court decisions in the developing state.

The stagnation in the execution of asset recovery has resulted in prolonged despair among fraud investment victims, forcing them to relinquish what the court initially guaranteed. This stagnation poses the risk that such judgments may not be enforced. This study is based on the following three arguments. First, financial penalties can be an effective component of punishment in investment fraud cases. Second, asset recovery is the right to invest in crime victims and should be done by the state. Third, regulatory integration in the criminal justice system is needed so that institutions do not become obstacles to each other. The trend of courts favouring asset recovery emerged in 2022 and 2023, with examples such as the First Travel case, the Binomo case, and the Quotex case. Referring to the CSI case in 2017, this is troublesome because asset recovery is seen as a euphoria of restorative justice that is developing in the Attorney General’s Regulation (2020) and the Police Regulation (2021) without realising that the Criminal Procedure Code and other regulations in the field of state finances do not allow for this to happen.

Method

The main objective of this study is to provide recommendations on what policies should be formulated to ensure asset recovery for victims of investment crimes. The main approach used in this study is a case approach, which is then elaborated upon with a statutory approach. The case being analysed is the CSI case, which is one of the major cases that occurred in the city of Cirebon, West Java Province, Indonesia. There are two reasons for choosing this case: firstly, because of the enormous losses incurred by the victims, 3 868 victims of investment crimes have been successfully re-registered, with a total investment value of IDR 336 894 270 000; and secondly, because this case could not be resolved until 2023, despite the fact that the court pronounced its decision in 2017. The case was studied using a statutory approach, examining how regulations related to restitution or victim protection were applied. Other cases that have been investigated in courts, such as the case involving Binomo and Quotex, have had a destructive impact on a smaller scale; discussing the execution of asset recovery in CSI cases can predict what challenges the other two cases will face.

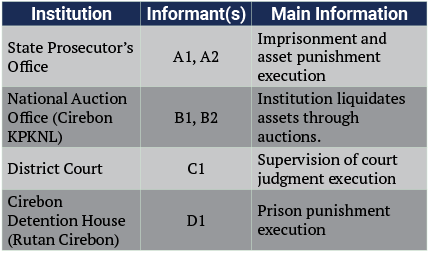

Primary data were obtained from interviews during 9 -13 January 2023, and secondary data were obtained by reviewing case files and references. The informants involved in the interviews were officials directly involved in the execution of punishment in the CSI case, namely:

Table 1. List of informants interview

Interviews A list of questions was prepared with specific topics on the current conditions in asset recovery execution, auction financing for asset recovery, and coordination between institutions in execution. The informants were selected by each institution; they received orders from the institution, which is a shortcoming in this research. However, all informants were confirmed to have handled executions in CSI cases. A review of regulations and references has been conducted in relation to asset recovery regulations and execution in Indonesia. The data collected were then reduced based on three sub-problems in the research assumptions: formulation of asset recovery regulations, state financial support in asset forfeiture auctions, and inter-institutional coordination in the criminal justice system. The data are displayed on Tables, in excerpts, and regulatory resumes. Content analysis was used in the discussion, and the data displayed in the results were identified on three topics that show how regulations and agencies respond to cases with new patterns, such as CSI. This method will lead to conclusions and recommendations for solving the problem of execution stagnation in future investment crime cases.

Results

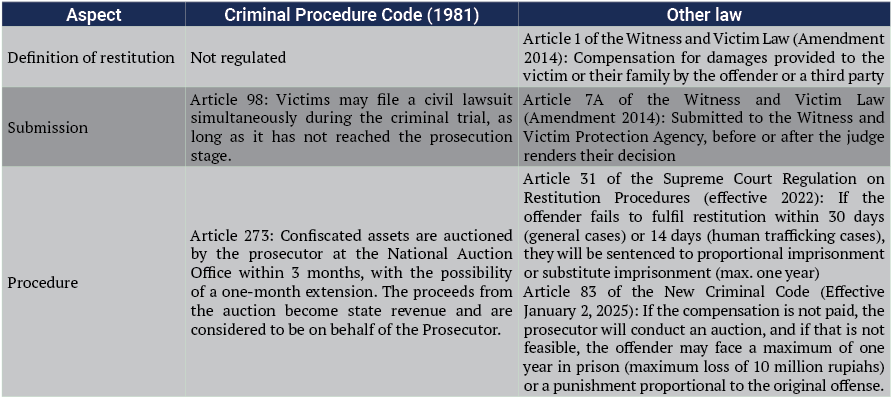

Restitution regulations insufficient to support asset recovery execution

Asset recovery for victims is still a relatively new concept in criminal proceedings in Indonesia. It was introduced in the first version of the Anti-Money Laundering Law (2002). In practice, it has only recently been implemented in cases related to corruption. The Law was updated in 2010, allowing for the prosecution of money laundering offenses without the need to first prosecute the predicate crime. Asset recovery for victims, which involves restitution, was also introduced more recently in 2006. The following are the restitution regulations outlined in various key legislations.

Table 2. Restitution regulations for financial crimes

The Code of Criminal Procedure (KUHAP), as the primary legal framework for trial practices, does not currently regulate restitution. This law was established in 1981 with the aim of protecting the rights of suspects due to widespread cases of torture. Therefore, its orientation is focused on safeguarding the rights of the accused. Asset forfeiture, in this context, does not intend to restore the rights of victims through restitution but rather serves as a punishment that contributes to state finances. The Law on the Indonesian Witness and Victim Protection Agency (LPSK), which first introduced provisions on restitution, was enacted in 2006. It was later revised in 2014 to accommodate restitution requests after a court verdict had been issued. This regulation was introduced because the LPSK was initially only based in Jakarta, the capital city. When the court grants a restitution request, the perpetrator is required to make an immediate voluntary payment, or else they may face an additional punishment of a maximum of one-year imprisonment. According to the law that will take effect on January 2, 2025, the consequence would be the seizure of the perpetrator’s assets and subjecting them to the same imprisonment period if asset seizure is not feasible.

The regulation of restitution in Indonesia is characterised as partial or fragmented. Law enforcement officials and the public must navigate through multiple regulations in order to facilitate the occurrence of restitution. The execution process following the grant of restitution involves the pursuit of the perpetrator’s assets. If these assets are non-monetary in nature, liquidation through auction at the State Auction Office is necessary. The success of this scheme heavily relies on the sales performance of the auction. This idea implies that the less attractive the seized assets are, the lower the probability of their sale. The implementation of the New Criminal Code in 2025 will not significantly alter the existing patterns, as the available execution scheme merely imposes a second imprisonment term of the same duration. Nevertheless, the restitution application scheme is designed to be more flexible, allowing prosecutors to directly file for restitution and relieving victims of the burden of dealing with the logistical challenges of travelling to Jakarta.

Asset recovery has not been fully integrated into the state financial system

This Case was recorded as No. 193/Pid.B/2017/PN Sbr and determined an unusual decision, confiscating the defendant’s assets not for the state but for the victim. Article 273 of the Indonesian Criminal Procedure Code only regulates the auction of confiscated goods for state purposes, which means that the auction proceeds become part of the state’s assets. In this decision, many assets can be distributed to the victims, as shown on Table 2. Five years after the decision was rendered in 2017, it was recorded that as of 2022, the data had found 3 868 victims. The panel of judges in the CSI case provided assurance of asset recovery for the victims, increasing the likelihood of restitution through the seizure of assets as a coercive measure. However, the execution of asset recovery has been significantly delayed and preceded by the completion of prison sentences for both perpetrators, which occurred on February 21, 2023. The main issue pertaining to asset recovery is the lack of financial support from the KPKNL (Ministry of Finance).

Table 3. List of asset recovery objects

The asset recovery execution was carried out by the Cirebon District Prosecutor’s Office. The assets that needed to be monitored inopportunely registered 58 properties for auctions. All confiscated items based on court decisions are auctioned through the Cirebon KPKNL; generally, these items are confiscated to become state income, so if items are confiscated for victims, the auction process must be borne by the auction applicant, namely the Prosecutor. Informant B1 (KPKNL Auction Officer) explained:

Based on Minister of Finance Regulation No. 64/PMK.06/2016 regarding Government Appraisers, appraisals can be conducted for assets seized by law enforcement, but must they aim to increase state wealth (non-tax state revenue/PNBP). As a consequence, the appraisal fee in the CSI case is not covered by the Ministry of Finance. According to Government Regulation No. 3 of 2018 regarding Types and Tariffs of PNBP, auction fees are also imposed. For land, the auction fee is 2 % for the seller and

2 % for the buyer, while for vehicles, there is a fee of 2.5 % for the seller and 3 % for the buyer. Payment can be made after the auction is completed. (Interview, B1, January 10, 2023)

Two components of auction financing, especially appraisal fees, would be inappropriate if they were borne by the victims. Even though the number of victims reached 3868, mobilising the number of victims to cover auction costs would be a significant challenge. Victims have experienced financial losses and psychological attacks; therefore, charging appraisal fees is inappropriate. The Cirebon District Prosecutor’s Office does not have the available budget to cover appraisal costs for 59 property objects, so the only way that can be a solution is to coordinate with the Attorney General’s Office (i.e., Kejaksaan Agung) through the Asset Recovery Centre (PPA). Informant A1 (Senior Prosecutor) explained:

We have coordinated with the Asset Recovery Centre of the Attorney General’s Office to finance the appraisal fee, and the appraisal is entrusted to a Public Appraisal Service Office (KJPP). On August 31, 2022, KJPP completed their work for 52 assets in Ciayumajakuning and one asset in Jakarta. Our target is to conduct the auction at the National Auction Office in February 2023, and if the assets are not sold, we aim to hold another auction in August 2023. (Interview, A1, January 9, 2023)

The financing scheme facilitated by the PPA requires a relatively long process, and the administration of state finances managed by the Attorney General’s Office requires various stages that take time. Based on Table 3, there are potential sources of funds that can be used to resolve the problem of paying appraisal fees, such as savings in the form of rupiahs and dollars. However, this source of funds does not include savings or deposits that can generate interest or profits and are prohibited from being used for borrowing. Informant A2 (Junior Prosecutor) provided the following information.

In the CSI case, the issue of the appraisal fee could be resolved if the seized assets in the form of a savings account amounting to IDR 25 222 524 747.85 were allowed to be used. The required budget is only IDR 200 000 000, but there is no regulation available for this policy. (Interview, A2, January 9, 2023)

The PPA’s involvement in executing asset recovery is limited to guaranteeing financing for the auction process; the auction results are not part of the success of the budgeting intervention. Auctions open sales that take place online, so the results of auction sales will be directly proportional to the level of public interest in buying the asset. The information previously conveyed by Informant A1 was that a 3rd stage auction would be held in 2023, whereas previously, a 2 - stage auction had been held, namely in 2021 (Stage 1) and 2022 (Phase 2), with relatively few interesting sales results. Informant B2 (KPKNL Legal and Information Officer) explained:

On February 1, 2021, the Cirebon KPKNL (State Property and Auction Office) had previously conducted an auction for 30 parcels of land and one vehicle belonging to CSI. In this auction, five items were successfully sold for a total sales value of IDR 499 147 000, and there were unsold items with a total value of IDR 41 429 780 000. Previously, on July 7, 2020, one item, SHM No. 520, was sold for IDR 139 500 000. There was only one bidder in that auction. (Interview, B2, January 10, 2023)

The presence of numerous assets available for recovery is a logical outcome of addressing the victims of investment fraud, which typically involves a substantial number of individuals. The consideration of auction fees to facilitate the liquidation of seized assets from the perpetrators should have been thoroughly evaluated during the trial proceedings rather than solely during the execution phase. Restitution within the Indonesian criminal justice system loses its significance when it cannot be fully implemented. Restitution often emerges as an assertion that the court’s decision favours the victims. The inadequacy of regulations governing the execution process renders the available resources ineffective despite the required costs representing a mere 0.008 % of these resources. This phenomenon can be characterised as the victim’s enduring victimisation for the third time: first during the occurrence of the crime, then due to their limited opportunities during the trial process, and finally, as they await the prosecution’s attainment of financing for the auction process.

Absence of judicial oversight in the execution

of judgments

The criminal justice system encompasses various subsystems, including the investigative phase (handled by the police), the prosecutorial phase (led by prosecutors), the judicial phase (conducted by the courts), and the execution phase (carried out by correctional institutions and the Ministry of Finance in relation to fines and auctions). The effective integration of these subsystems relies on the Prosecution Office assuming a controlling role (dominus litis) while being overseen by the Judiciary. The criminal justice system in Indonesia consists of four subsystems: investigation, prosecution, trial, and execution. Integrality between all subsystems occurs up to the execution stage. The Indonesian Criminal Procedure Code regulates that the court must assign a judge whose duty it is to supervise and observe court decisions executed by the Prosecutor. However, Article 280 regulates that the sentences supervised and observed are limited to prison sentences. Asset recovery for victims is a follow-up to the sentence for confiscation of goods; as a result, asset recovery efforts are only carried out independently by the prosecutor. Informant A1 (Senior Prosecutor) explained:

The Court has never conducted monitoring and evaluation, even though the execution has been ongoing for years. At the very least, we need a proportional distribution interpretation for the victims. However, we have not prioritised this need as the auction is incomplete. (Interview, A1, January 9, 2023)

The coordination procedure for the auction of confiscated goods does not involve the court, but only occurs between the Prosecutor’s Office as the auction applicant and KPKNL as the auction organiser. The court has not focused on ensuring that the Prosecutor’s Office and KPKNL are able to meet the victims’ expectations regarding asset recovery, which has been justified by the court decision. Informant B1 (KPKNL Auction Officer) explained:

We have not coordinated with the Court. Usually, we only coordinate with the Prosecutor’s Office for asset auctions in criminal cases. (Interview, B1, January 10, 2023).

The execution of prison sentences that fell within the scope of the judge’s supervision and observation was not carried out by the court, and based on an examination of the files, there was no indication that the court had assigned a judge to evaluate the convicts. The convicts of this crime serve prison sentences at the Cirebon Detention House without being supervised by the court, so there is no evaluation process of whether the prison sentence has a positive impact on the convicts or an evaluation of the extent to which the convicts help the prosecutor carry out asset recovery for the victims. Informant D1 from the Cirebon Detention Centre explained:

Regular monitoring is conducted by the District Court, but it seems that no monitoring was carried out for the two convicts as no files were found. According to the standard operating procedure, if monitoring was conducted, the files would be available. The results of monitoring for other convicts were also not communicated to us. (Interview, D1, January 13, 2023)

This information is in accordance with that obtained from C1 Informant from the District Court.

No supervisory and monitoring files were found for both convicts in the CSI case. The three judges who served on the panel have all been transferred to other assignments. (Interview, C1, January 11, 2023)

The criminal justice system in Indonesia continues to prioritise imprisonment as the primary form of punishment, disregarding the potential benefits of asset seizure as evidenced by legal developments. Furthermore, the courts fail to acknowledge the importance of rehabilitating offenders within correctional facilities, instead allowing these processes to occur in detention centres, which is a violation of the law. The monitoring and evaluation activities are conducted perfunctorily, with superficial visits considered sufficient to fulfil these responsibilities, lacking substantive discussions on improving rehabilitation programmes. The five-year timeframe provided for prosecutors to revalidate the number of victims further underscores the shortcomings of court decisions in effectively resolving conflicts. Even after the successful completion of auctions, prosecutors encounter challenges implementing payment distribution mechanisms for the victims. These two significant issues highlight a peculiar phenomenon where judges rely on their decisions to speak for themselves, assuming that all execution difficulties faced by prosecutors will be resolved through the provision of court rulings alone.

Discussions

Victims’ access to asset recovery for fairness law enforcement

Victims’ access to asset recovery for fairness law enforcement

Combatting investment fraud through the criminal justice system has the dimension of deterring perpetrators and accommodating the recovery of losses for victims. Referring to practices in the European Union, combatting these crimes is claimed to restore consumer confidence regarding engagement in internal market transactions (Díez & Herlin-Karnell, 2018). To provide a deterrent effect, manpower and resources are needed, such as the establishment of financial intelligence to prosecute all those who play a significant role in financial fraud (Hurwitz, 2019; Suxberger & Pasiani, 2018). On the other hand, the victim aspect is potentially forgotten. Victims tend to be seen as greedy and gullible people who are not in the “ideal victim” perspective (Cross, 2016; Nataraj-Hansen, 2024). This perspective is disproportionate as investment crime in the Indonesian context occurs due to an exceedingly high social inequality, thus the temptation to get rich quickly can work for those with sufficient financial literacy (Prabowo, 2024). The unlawful gains made by CSI resulted in widespread victimisation and massive financial losses, so proportionality in the criminal justice system is to prosecute the perpetrator to restore the victim’s losses.

The optimal legal protection for victims of economic crimes is achieved through asset recovery, as prison sentences for offenders offer only temporary and illusory satisfaction. The process of asset recovery for victims involves two problematic aspects: the policies governing asset seizure and asset management (Zolkaflil et al., 2023). The complexity of these issues has implications for creating incentives for offenders to cooperate in facilitating asset recovery and potentially receiving reduced sentences (Korejo et al., 2023). Research on asset recovery emphasises three key points. Firstly, the policy of seizing assets from convicted individuals should not be driven by the objective of increasing state wealth (Lara, 2020). Secondly, the absence of clear legal provisions for asset recovery leads to regulatory inconsistencies and challenges (Qisa’i, 2020). Thirdly, achieving effective asset recovery necessitates the alignment of paradigms to facilitate the harmonisation of collective strategies (Sakellaraki, 2022). This study reveals that the execution of asset recovery in the investment fraud case is hindered by the limited harmonisation of strategies, primarily within the prosecution institution. Despite the lack of adequate legal provisions, the initiation of asset recovery is primarily driven by this institution.

The establishment of legal provisions is a crucial step in ensuring that victims have access to asset recovery. At present, victims can only seek recourse through civil litigation, which they must address on their own (Lupianto, 2022). These legal provisions serve as the foundation for the criminal justice system’s policies, guaranteeing the availability and sufficiency of resources and promoting a shared approach (Akinsulorea, 2020). Several key considerations should be taken into account when formulating these legal provisions. Firstly, the court should determine the value of the losses and assets eligible for restitution, and it can direct the State Auction Office to facilitate this process (Bhatty, 2016; Dietrich Hill, 2013). Secondly, the court can appoint a trustee and receivers to enable more flexible assessment tasks, thereby alleviating the prosecution’s sole responsibility for execution (Linn, 2007). Thirdly, in situations where the second aspect is not feasible, the state can provide compensation funds through government bonds (Firmansyah et al., 2022). Consequently, the design of legal provisions for asset recovery should encourage collaboration among various agencies, with each institution having a guiding strategy to guide their work.

From a comparative perspective, Singapore can be seen as a benchmark. As a trading hub in the ASEAN region, international funds flow through and have the potential to become the subject of asset recovery. Asset recovery in fraud cases can use a scheme that orders the perpetrator to compensate the victim, as part of the punishment. This scheme aims for practicality, considering the complexity of filing a civil lawsuit (Ling & Xinying, 2021). According to Article 360 of the Singapore Criminal Procedure Code 2010, there are several methods of executing compensation that differ from Indonesia:

- Appointing a party with no interest in the case to act as the owner or seller of the confiscated property. The outcome of this appointment is then used to settle the compensation;

- Ordering parties who have matured debts to the Perpetrator to make payment to the Court to settle the compensation; and

- Issuing an Arrest Warrant if the perpetrator does not pay the compensation; this warrant is an agreement signed by the perpetrator with the court.

Auction financing in the execution of asset recovery by state finances

Asset recovery for victims signifies a paradigm of deviating from established norms to foster progressive court rulings. Judges actively participate in conflict resolution, dispute management, and social control through the establishment of innovative regulations (Mather, 2021). Going beyond the conventional belief that punishment should solely target offenders, accommodating the diverse interests of victims aims to restore their circumstances (Malsch & Carrière, 1999). Within the realm of Indonesian courts, assets seized in investment fraud cases are typically confiscated in favour of the state, as exemplified by the First Travel and Binomo cases. In the First Travel case (2017), the District Court in 2018 stated that the confiscation of assets was given to the state because the assets were the proceeds of crime and the victim data was unclear. This argument was examined and upheld in the same year by the High Court and Supreme Court (Putri et al., 2023). An anomalous phenomenon in 2022 occurred in the Supreme Court, where a previous decision was overturned because confiscated assets came from the victims, so they were the most rightful recipients thereof (Mahkamah Agung, 2022). Similarly, in the Binomo case, the district court seized assets for the state, perceiving Binomo’s clients as gamblers rather than victims of fraud. Nevertheless, the High Court later reversed this decision, prioritising the principles of equity, accuracy, and justice. Similarly, in the Binomo case (2022), the District Court 2022 seized the assets for the state, as it considered Binomo’s clients to be gamblers and not victims of fraud. In the same year, the Court of Appeal revoked the decision, arguing that it prioritised the principles of equality, accuracy, and fairness, which the Supreme Court upheld in 2023 (Mahkamah Agung, 2023). The trend towards accommodating asset recovery as a victim’s right is beginning to be recognised in the criminal justice system; however, this trend must also be recognised in the state financial system because auctions are an authority in that system.

The process of liquidating spoils of crime is necessary to make it easier to distribute the proceeds of asset recovery. Criminal punishment oriented towards the seizure of goods aims to restore the losses caused by crime and reduce public unrest (Parlindungan S, 2018). The development of the concept of the seizure of goods has now led to the seizure of goods without a court decision or without proving a predicate crime (Fauzia & Hamdani, 2022). This development in the criminal justice system is not linear with the development of the state financial system, and the results of this study show that state intervention in auctions occurs only when the state receives revenue from auction sales. The criminal justice system is designed to respond to public threats, and the unavailability of resources to achieve this goal reflects the lack of coordination and cooperation between institutions (Akinsulorea, 2020). Thus, Indonesia does not yet have a criminal justice system integrated with the state financial system, as can be seen from the obstruction of financial support in the execution of asset recovery.

Currently, access to justice for victims of investment crime cannot rely on the civil justice system. The use of civil law instruments is carried out through a bankruptcy scheme, which has the same characteristics as asset recovery because the seized assets are sold at auctions. The World Bank studied the effectiveness of bankruptcy in 2006 through the Doing Business 2006 survey, and it reached 18 % of bankruptcy objects with an average settlement of six years; however, the asset recovery rate only reached 13.1 % (The World Bank, 2006). Although this survey has not been updated again, the development of literature in Indonesia still claims that the cost of litigation in court is contrary to the principles of simplicity, and a speedy and low-cost trial (Aristeus, 2020; Nugroho, 2021; Sasanti & Indah, 2022). In general, victims experience various losses, such as physical, financial, and relational losses (Van Ness & Strong, 2015); in financial fraud, the specific impact that occurs is increased financial stress and complications following their victimisation experience. The indicator that a court decision has the value of justice is that the procedure should not be expensive (Lehtonen & Sutela, 2022). In reality, the criminal justice system takes a long time and has not yet found a comprehensive solution for asset recovery. However, various efforts have been made, such as technology usage to accelerate the process, mutual legal assistance for asset tracing, and even cooperation with the defendant for more optimal recovery (Febby Mutiara & Santoso, 2021; Korejo et al., 2023). Considering that state intervention only occurs when the auction generates state revenue associated with the inefficient use of civil schemes, an option that can be offered is a profit-sharing scheme for state revenue in asset recovery auctions.

Expanding of the scope of judge supervision and observation

The establishment of a comprehensive criminal justice system relies on more than just the adjudication of cases in court; it necessitates the effective execution of judgments. Judges should not simply rely on their decisions alone but instead consider the practicalities of implementation, considering clear and unbiased factors (Allioui, 2022). The purpose of the criminal justice system is to address public threats, requiring sufficient and accessible resources that can only be achieved through collaborative efforts between different institutions (Akinsulorea, 2020). However, the execution of judgments in the CSI case has encountered various challenges, such as incomplete regulations, inadequate funding for auctions, and ineffective mechanisms for judicial oversight. The absence of these issues in the Criminal Procedure Code has resulted in Ministry of Finance regulations that do not facilitate the availability of funds for asset recovery. As a result, imprisonment was completed before the property sentence was executed, leading to a paradoxical situation in which victims saw the perpetrators integrate into society. However, the right to claim confidentiality had been lost as the execution process was still ongoing. This fact raises doubts about the criminal justice system as the length of the execution process indicates a potential failure.

The court not only acts as an institution that decides on a criminal case filed by the prosecutor but also oversees the execution of the decision. The ultimate goal of the criminal justice system is to restore victims to their pre-crime state as much as possible (Gaines & Miller, 2016). The widespread publicity of executions can indicate the deterrent and symbolic effects of punishments (Hochstetler, 2001). Supervision and observation activities in the execution of judgments provide opportunities for coordination and cooperation among law enforcement agencies (Timoera, 2018). The handling of crime-money cases appears to have shifted away from addressing the needs of victims to obtaining asset recovery (Duyne et al., 2014). Victims do not receive sufficient legal protection, which results in a lack of mental and physical security from the various disturbances that afflict society (Rahardjo, 2014). The Indonesian Criminal Procedure Code’s design overly restricts the activities of supervision and observation of imprisonment, although both activities aim to reduce the gap between decision and execution (Maroni, 2016). In this case, the idea of expanding judges’ supervision and observation of the execution of decisions is logical and can potentially reduce various obstacles to the execution of asset recovery.

The court’s role in execution is a crucial issue in Indonesia, which may never be discussed in other states, especially in developed states. In practice, execution is performed in both criminal and civil cases. According to Article 277 of the Criminal Procedure Code, the court assigned a special judge to supervise and observe the imprisonment decision. According to Article 280 of the Criminal Procedure Code, supervision aims to ensure that the verdict has been implemented properly, and observation aims to examine the benefits of the verdict on changes in the behaviour of the convict during the period of imprisonment. In Article 54 of the Judicial Power Law, civil cases are executed by the Registrar and Bailiff. The contrasting difference between the two types of cases is that in criminal cases, the judge is tasked with rendering and supervising a decision. In the practice of criminal cases, Supervision and Observation Judges (Wasmat Judges) experience obstacles such as the small number of judges, the lack of understanding of judges in monitoring and evaluation duties, and work carried out individually (Panggabean et al., 2024). In the practice of civil cases, the Registrar’s team works to carry out executions, and there is cooperation with the Police and the Military if there are efforts to obstruct the execution (Hartati & Syafrida, 2021). Asset recovery in investment fraud cases is a case with criminal and civil aspects; the criminal aspect is contained in confiscation, and the civil aspect is contained in the sale and handover of auctioned property; the combination of these two aspects can be considered a new design in the execution of asset recovery, in which the Court appoints a Supervisory and Observer Team consisting of Wasmat Judge, Bailiff, and Registrar.

Conclusion

This study shows that court decisions are insufficient to ensure that asset recovery is accessible to victims of investment fraud. The execution of asset recovery has stagnated due to the unavailability of sufficient resources and the absence of inter-institutional coordination; consequently, execution indicates the phenomenon of “judges letting their verdicts speak for themselves.” The court did not take the role to intervene in the issue of auction financing in asset liquidation between the Prosecutor and the Ministry of Finance because the supervision of the execution of sentences has been limited to imprisonment. This flow is contradictory because, under supervision, the Court does not evaluate these offenders’ behavioural improvement or how they cooperate facilitating execution. The use of civil litigation, such as bankruptcy, is not suitable in this case in Indonesia; it will increase the financial loss due to other costs and requires victim mobilisation by establishing a victim community. Finally, asset recovery is only an idealisation that the criminal justice system has responded progressively to the needs of victims while forgetting about the ability to execute.

This article recommends that Indonesia prepare for overhauling the criminal justice system so that it focuses on inter-agency cooperation in order to mitigate the risk of non-execution. The comprehensive steps are as follows:

- Recognise asset recovery as a right for victims of financial crime and not limit it to corruption cases.

- Design a monitoring and evaluation scheme from for the Court to the Prosecutor and other institutions to facilitate the liquidation of assets through auctions. Referring to the execution of imprisonment and civil cases, the Supreme Court can formulate a policy to assign special officers, namely Supervisory Judges and Bailiffs. The practice in both executions to date is still ongoing, so the task of supervising asset forfeiture auctions is at a reasonable performance burden; and

- The Ministry of Finance facilitates the liquidation of assets by covering appraisal costs and auction costs, which can be charged to victims through the profit-sharing option after the auction is completed. Victims do not need to bear the costs of this process because the criminal justice system has the consequence that the victim has handed over the case to the Prosecutor.

These three steps begin with revising the Criminal Procedure Code, followed by synchronising regulations between Asset Forfeiture Law and State Finance Law. This regulatory revision will be prolonged and cost money. However, it is believed that it can build a new paradigm in the criminal justice system that is able to respond to the needs of victims of financial crime more humanely, as well as being an instrument to prove that the state is present in responding to investment fraud.

This research has limitations in the victim aspect because it only focuses on discussing victims’ rights from the perspective of state institutions. Obtaining primary data directly from the victims and the two perpetrators is still a challenge that has not yet been resolved. CSI is a sensitive case; February 21, 2023, is the moment when the two perpetrators finish their prison terms, and a massive number of victims often visit their homes and cause social disruption for the surrounding neighbours. Further research based on the perspective of victims and perpetrators is expected to complement this study by exploring the contribution of perpetrators and victims to complete the execution of asset recovery.

Conflict of interest

We declare that we do not have any financial or personal relationship that could influence the interpretation and publication of the results obtained. Likewise, we ensure that we comply with ethical standards and scientific integrity at all times, in accordance with the guidelines established by the academic community and those dictated by this journal.

References

Akers, M. D., & Gissel, J. L. (2006). What Is Fraud and Who Is Responsible? Journal of Forensic Accounting Profession, 7(1), 247-256. https://core.ac.uk/download/213082859.pdf

Akinsulorea, A. (2020). The Nigeria police philosophy and administration of criminal justice post 2015: Interrogating the dissonance. Sriwijaya Law Review, 4(2), 136-153.

Ali, S. (2020). Fighting financial crime: failure is not an option. Journal of Financial Crime. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFC-04-2019-0050

Allioui, S. (2022). How to Measure the Quality of Judicial Reasoning? International Journal for Court Administration. https://doi.org/10.36745/ijca.396

Arief, B. N. (2008). Bunga Rampai Kebijakan Hukum Pidana, Perkembangan Penyusunan KUHP Baru. Kencana, Jakarta.

Aristeus, S. (2020). Eksekusi Ideal Perkara Perdata Berdasarkan Asas Keadilan Korelasinya Dalam Upaya Mewujudkan Peradilan Sederhana, Cepat dan Biaya Ringan. Jurnal Penelitian Hukum De Jure. https://doi.org/10.30641/dejure.2020.v20.379-390

Bhatty, I. (2016). Navigating paroline’s wake. UCLA Law Review.

Brun, J.-P., Sotiropoulou, A., Gray, L., & Scott, C. (2021). Asset Recovery Handbook: A Guide for Practitioners, Second Edition. In StAR Initiative Ser.

Cassella, S. D. (2019). Nature and basic problems of non-conviction-based confiscation in the United States. Veredas Do Direito. https://doi.org/10.18623/rvd.v16i34.1334

Chistyakova, Y., Wall, D. S., & Bonino, S. (2021). The Back-Door Governance of Crime: Confiscating Criminal Assets in the UK. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10610-019-09423-5

Cross, C. (2016). “They’re very lonely”: Understanding the fraud victimisation of seniors. In International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy. https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcjsd.v5i4.268

De Londras, F., & Dzehtsiarou, K. (2017). Mission Impossible? Addressing Non-Execution Through Infringement Proceedings in The European Court of Human Rights. International and Comparative Law Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002058931700001X

Deb, S., & Sengupta, S. (2020). What makes the base of the pyramid susceptible to investment fraud. Journal of Financial Crime, 27(1), 143-154. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFC-03-2019-0035

Dewi, K. R., Hartiwiningsih, H., & Novianto, W. T. (2018). Follow the Money as an Attempt of State Financial Loss Restoration in Criminal Action of Money Laundering with Corruption as Predicate Crime. International Journal of Multicultural and Multireligious Understanding. https://doi.org/10.18415/ijmmu.v5i3.403

Dietrich Hill, T. (2013). The arithmetic of justice: Calculating restitution for mortgage fraud. Columbia Law Review, 113(11), 1939-1976. https://columbialawreview.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Hill.pdf

Díez, C. G. J., & Herlin-Karnell, E. (2018). Prosecuting EU Financial Crimes: The European Public Prosecutor’s Office in Comparison to the US Federal Regime. German Law Journal. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2071832200023002

Doig, A. (2013). What is fraud? In Fraud (pp. 37-59). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781843926115-9

Duyne, P. C. van, Zanger, W. de, & Kristen, F. (2014). Greedy of Crime-Money. The Reality and Ethics of Asset Recovery. In Corruption, Greed and Crime-money. Sleaze and shady economy in Europe and beyond (pp. 235-266). Wolf Legal Publishers. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2474113

Fauzia, A., & Hamdani, F. (2022). Analysis Of The Implementation Of The Non-Conviction-Based Concept In The Practice Of Asset Recovery Of Money Laundering Criminal Act In Indonesia From The Perspective Of Presumption Of Innocence. Jurnal Jurisprudence. https://doi.org/10.23917/jurisprudence.v11i1.13961

Febby Mutiara, N., & Santoso, T. (2021). Principle of Simple, Speedy, and Low-Cost Trial and The Problem of Asset Recovery in Indonesia. Indonesia Law Review, 11(2), 117-135.

Firmansyah, Y., Imam Haryanto, Tubagus Andri Purnama, & Edwin Destra. (2022). Compensation for Fraud (Gambling) Operations Under The Guise of Investment - Restitution as A Complex or Easy Way Out Mechanism? (Learning From Various Restitution And Law Cases In Indonesia). East Asian Journal of Multidisciplinary Research. https://doi.org/10.55927/eajmr.v1i3.280

Gaines, L. K., & Miller, R. L. (2016). Criminal Justice in Action: The Core (9th ed.). Cengage Learning. https://faculty.cengage.com/works/9781337092142

Green, S. T., Kondor, K., & Kidd, A. (2020). Story-telling as memorialisation: Suffering, resilience and victim identities. Onati Socio-Legal Series. https://doi.org/10.35295/osls.iisl/0000-0000-0000-1122

Hamzah, A. (2008). Hukum Acara Pidana Indonesia Edisi Kedua. In Jakarta: Sinar Grafika.

Hartati, R., & Syafrida, S. (2021). HAMBATAN DALAM EKSEKUSI PERKARA PERDATA. ADIL: Jurnal Hukum. https://doi.org/10.33476/ajl.v12i1.1919

Hochstetler, A. (2001). Reporting of executions in U.S. newspapers. Journal of Crime and Justice. https://doi.org/10.1080/0735648X.2001.9721614

Hurwitz, M. H. (2019). Focusing on deterrence to combat financial fraud and protect investors. Business Lawyer.

Junqueira, G. M. (2020). The assets recovery, the mutual recognition scheme and the requests for judicial cooperation related to non-conviction based forfeiture in Portugal. Revista Brasileira de Direito Processual Penal. https://doi.org/10.22197/rbdpp.v6i2.294

Kaniki, A. O. J. (2021). The Role of Criminal Investigation in Facilitating Asset Recovery in Economic Crime in Tanzania. Eastern Africa Law Review. https://doi.org/10.56279/ealr.v48i1.5

Korejo, M. S., Rajamanickam, R., Md. Said, M. H., & Korejo, E. N. (2023). Plea bargain dilemma, financial crime and asset recovery. Journal of Money Laundering Control, 26(3), 628-639. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMLC-01-2022-0009

Lacey, D., Goode, S., Pawada, J., & Gibson, D. (2020). The application of scam compliance models to investment fraud offending. Journal of Criminological Research, Policy and Practice, 6(1), 65-81. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCRPP-12-2019-0073

Lambert-Abdelgawad, E. (2002). The Execution of Judgments of The European Court of Human Rights. Council of Europe Publishing. https://www.echr.coe.int/documents/d/echr/Pub_coe_HFfiles_2002_19_ENG

Lara, F. J. P. (2020). Asset recovery law in Mexico: Revision of its constitutional and conventional structure. In Revista Brasileira de Direito Processual Penal. https://doi.org/10.22197/rbdpp.v6i2.351

Lehtonen, O., & Sutela, M. (2022). Geospatial Research Supporting Decision-Making in Court Services - an Assessment of the 2019 District Court Reform in Finland. International Journal for Court Administration, 13(3). https://doi.org/10.36745/ijca.385

Ling, L. M., & Xinying, C. (2021). The Asset Tracing and Recovery Review: Singapore. In R. Hunter (Ed.), The Laws Review (9th ed., pp. 278-295). Law Business Research Ltd. https://assets.ctfassets.net/wwqh0hdhnyw9/7EVeTD97XiOfBT6j8p1Q6r/ddc6de967d98064bb024b7b1177e2f97/Liechtenstein.pdf

Linn, C. J. (2007). What asset forfeiture teaches us about providing restitution in fraud cases. Journal of Money Laundering Control, 10(3), 215-276. https://doi.org/10.1108/13685200710763452

Lupianto, E. N. (2022). Asset Recovery for Victims of “Binary Option” Case in Review of International Criminal Law. Corruptio, 3(1), 47-60. https://doi.org/10.25041/corruptio.v3i1.2640

Mahkamah Agung. (2022). Andika Surachman et al Case (First Travel). Direktori Putusan. https://putusan3.mahkamahagung.go.id/direktori/putusan/zaedff611463b25899ea313031333133.html

Mahkamah Agung. (2023). Indra Kenz Case (Binomo). Direktori Putusan. https://putusan3.mahkamahagung.go.id/direktori/putusan/zaed91961c11dd56b545313635353432.html

Malsch, M., & Carrière, R. (1999). Victims’ wishes for compensation: The immaterial aspect. Journal of Criminal Justice. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0047-2352(98)00062-2

Maroni, M. (2016). Tinjauan Yuridis Eksistensi Hakim Pengawas Dan Pengamat Dalam Sistem Peradilan Pidana Indonesia. FIAT JUSTISIA:Jurnal Ilmu Hukum. https://doi.org/10.25041/fiatjustisia.v1no2.671

Mather, L. (2021). What is a “case”? Onati Socio-Legal Series. https://doi.org/10.35295/OSLS.IISL/0000-0000-0000-1149

Nataraj-Hansen, S. (2024). “More intelligent, less emotive and more greedy”: Hierarchies of blame in online fraud. International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlcj.2024.100652

Novokmet, A. (2016). The right of a victim to a review of a decision not to prosecute as set out in article 11 of directive 2012/29/eu and an assessment of its transposition in Germany, Italy, France and Croatia. Utrecht Law Review. https://doi.org/10.18352/ulr.330

Nugroho, I. (2021). Asas Peradilan Sederhana, Cepat, dan Biaya Ringan terhadap Penyelesaian Sengketa Ekonomi Syariah melalui Gugatan Sederhana. Jurnal Al-Hakim: Jurnal Ilmiah Mahasiswa, Studi Syariah, Hukum Dan Filantropi, 3(1), 13-30. https://doi.org/10.22515/alhakim.v3i1.3896

Panggabean, H., Simanjuntak, F., & Rajagukguk, H. (2024). Legal Review of the Role Supervisory Judges and Observer towards Convicts Who is Sentenced to Conditional Punishment. International Journal of English Literature and Social Sciences. https://doi.org/10.22161/ijels.92.2

Parlindungan S, G. T. (2018). Pelaksanaan Lelang Barang Sitaan Oleh Komisi Pemberantasan Korupsi. SUPREMASI Jurnal Hukum. https://doi.org/10.36441/supremasi.v1i1.156

Pavlidis, G. (2023). Global sanctions against corruption and asset recovery: a European approach. Journal of Money Laundering Control. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMLC-10-2021-0120

Pengadilan Negeri Sumber. (2017). Decision No. 193/ Pid.B/2017/PN Sbr. Sistem Infomrasi Penelusuran Perkara. https://sipp.pn-sumber.go.id/

Prabowo, H. Y. (2024). When gullibility becomes us: exploring the cultural roots of Indonesians’ susceptibility to investment fraud. Journal of Financial Crime. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFC-11-2022-0271

Putri, A. S., Danil, E., & Mulyati, N. (2023). Legal Protection Application of Victims Through a Combined Lawsuit for Compensation in Case of Criminal Acts of Fraud and Money Laundering (Case Study: PT First Travel Cassation Decision Number 3096 K/Pid.Sus/2018). International Journal of Multicultural and Multireligious Understanding, 10(4), 398-405. https://ijmmu.com/index.php/ijmmu/article/view/4533

Qisa’i, A. (2020). Sustainable Development Goals (SDGS) And Challenges Of Policy Reform On Asset Recovery In Indonesia. Indonesian Journal of International Law. https://doi.org/10.17304/ijil.vol17.2.785

Rahardjo, S. (2014). Ilmu Hukum. In PT Citra Aditya Bakti.

Ramos, V. C., & Pereira Coelho, D. (2023). Defending victims of cross-border fraud in the EU - A Portuguese view, including the use of preventive “freezing” of bank accounts under anti-money laundering legislation. New Journal of European Criminal Law. https://doi.org/10.1177/20322844231173913

Sakellaraki, A. (2022). EU Asset Recovery and Confiscation Regime - Quo Vadis? A First Assessment of the Commission’s Proposal to Further Harmonise the EU Asset Recovery and Confiscation Laws. A Step in the Right Direction? New Journal of European Criminal Law, 13(4), 478-501. https://doi.org/10.1177/20322844221139577

Sasanti, D. N., & Indah, H. T. K. (2022). Problematika Penyelesaian Sengketa di Pengadilan Pajak Dalam Rangka Perwujudan Peradilan Sederhana, Cepat, dan Biaya Ringan. Reformasi Hukum, 26(1), 21-38. https://doi.org/10.46257/jrh.v26i1.256

Sittlington, S., & Harvey, J. (2018). Prevention of money laundering and the role of asset recovery. Crime, Law and Social Change. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-018-9773-z

Suud, A. K. (2020). Optimization of The Role of Asset Recovery Center (PPA) of The Attorney-General’s Office of The Republic of Indonesia in Asset Recovery of Corruption Crime Results. Jurnal Hukum Dan Peradilan. https://doi.org/10.25216/jhp.9.2.2020.211-231

Suxberger, A. H. G., & Pasiani, R. P. R. (2018). The role of financial intelligence in the persecution of money laundering and related felonies. Revista Brasileira de Politicas Publicas. https://doi.org/10.5102/rbpp.v8i1.4618

Tasdikin, Y. L., & Wahyudi, S. T. (2022). Problems of The Settlement of State Looted Goods in The Criminal Act of Corruption and Money Laundering at PT Asuransi Jiwasraya. Indonesian Journal of Multidisciplinary Science. https://doi.org/10.55324/ijoms.v1i10.186

Taufiq, A. I. (2016). Pelaksanaan Tugas Hakim Pengawas dan Pengamat Pengadilan Negeri Yogyakarta bagi Narapidana Penjara di Lapas Wirogunan dan Lapas Narkotika. Supremasi Hukum: Jurnal Kajian Ilmu Hukum.

The World Bank. (2006). Doing Business in 2006: Creating Job. https://www.doingbusiness.org/content/dam/doingBusiness/media/Annual-Reports/English/DB06-FullReport.pdf

Thomas, J., Rasmussen, D. W., & Benson, B. L. (1995). The Economic Anatomy of a Drug War: Criminal Justice in the Commons. The Economic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2307/2235169

Timoera, D. A. (2018). Peran Dan Tanggung Jawab Hakim Wasmat Terkait Perlindungan Hak-Hak Narapidana Dalam Lembaga Pemasyarakatan. Jurnal Ilmiah Mimbar Demokrasi, 14(1), 43-58. https://doi.org/10.21009/jimd.v14i1.6506

Van Ness, D. W., & Strong, K. H. (2015). 1 - Visions and Patterns: How Patterns of Thinking Can Obstruct Justice. Restoring Justice.

Wibowo, A. (2023). Barriers and solutions to cross-border asset recovery. Journal of Money Laundering Control. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMLC-01-2022-0022

Zolkaflil, S., Syed Mustapha Nazri, S. N. F., & Omar, N. (2023). Asset recovery practices in combating money laundering: evidence from FATF mutual evaluation report of FATF member countries of Asia pacific region. Journal of Money Laundering Control. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMLC-11-2021-0127