Introduction

Cangaço emerged in northeastern Brazil between the years 1870 and 1940 and became known as a violent variant of organized crime. The cangaceiros, as the agents of these crimes were known, surrounded small towns, spread panic, killed, stole, kidnapped, and fled, before or after clashes with the local police. The page was only turned on this type of crime when police task forces had eliminated all gangs. It is worth noting that this movement was a social, political and cultural phenomenon that occurred in the northeastern Sertão, which we can classify as an organized crime practice. The cangaceiros were hired to carry out robberies, kidnappings, and executions at the behest of local political leaders.

The cangaço gained strength from 1889 onwards, with the Proclamation of the Republic and the change from centralized power in Rio de Janeiro to local power, commonly exercised by colonels. Bands of cangaceiros committed various crimes in the places they passed through, such as robberies, murders, rapes, and mutilations, among many others.

In mid-2015, gangs specializing in bank robberies resumed this mode of operation in cities in the northeast and southeast of Brazil, in a new wave of crimes called the new cangaço. The media quickly associated such criminal acts with modern terrorism. Even though these acts are permeated with extreme violence including use of explosives, high-caliber weapons, drones, improvised explosive devices, use of human shields, and contempt for the local police force, such criminals are not considered terrorists under Brazilian law.

In this context, the aim of this article is to discuss the new cangaço as a new order of organized crime and its similarity to the concept of global terrorism. We used the analysis of scientific articles and interviews with professionals in special operations, such as bank robbery, cybercrime, and property crimes to carry out this research.

In this way, we contribute to theory for investigating terrorism and practices that fight organized crime. We fill an anticipated gap in the security and defense literature that has not yet highlighted the relationship between organized crime, bank robbery, and terrorism.

Our research presents a theoretical reference centered on terrorism, new cangaço, and Brazilian laws. To continue, we describe our method and carry out analysis and discussion.

Theoretical reference

Terrorism often involves an act of violence. This statement may sound obvious, however in practice it is not, as cases of environmental terrorism and cyber terrorism are becoming more and more frequent. In an expanded form, terrorism corresponds to a threat intended to coerce, intimidate or dissuade a third party (González et al., 2016). Furthermore, a terrorist group acts by copying the success of another terrorist group (Makarenko, 2004), in the world of weak or bankrupt institutions with a high level of corruption and criminality and the absence of effective and independent law enforcement.

A series of important publications have mapped out the definitions and possible variations of terrorism (Fehr & Schimidt, 1999; Merari, 1994; Primoratz, 1990; Ruby, 2002; Schmid, 2011), among them, the classification that predicts the size of the units involved, the weapons used, the tactics, and the targets. This classification is still current today and is foreseen in strategies for preventing and combating terrorism: (a) size of combat units – small (normally less than 10 elements, (b) weapons – use of light firearms, possibly grenades, (c) tactics – kidnappings, car bombs and assassination, (d) targets – government buildings, random people, politicians and adversaries, (e) territory control – no, (f) uniform – none, (g) delimitation of operations – none, (h) legality – no, (i) domestic – no, and (j) expected impact – psychological coercion (Merari, 1991; 1993; 1994).

From 1945 onwards, terrorism was perceived as tactical actions, from 1960 it was seen as bomb attacks, in the following decade, as the hijackings of commercial planes, and in the 1980s and 1990s, attacks of both types, with terrorism adapting to the political and technological context of the day; that is, seeking to obtain the greatest possible strategic advantages. In the academic context, terrorism is mainly identified as a political and violent action (Suarez, 2012). Therefore, the concept is in a constant state of development. Furthermore, research shows that organized crime joins forces with terrorist groups with the aim of emboldening criminal operations. (Hutchinson, O’malley, 2007).

Terrorism manifests itself through attacks with explosive devices, biological, chemical, and radioactive substances, as well as in kidnappings and the robbery of financial institutions. The consequences left for the population are most diverse and include trauma and post-traumatic stress. Generally, terrorist practices aim to draw attention to a cause. The idea is to provoke fear and shock among the victims and at the same time satisfaction, applause, and consent from allies (Bock, 2009). All these points became more evident from the beginning of the 21st century.

The September 11 attacks profoundly changed the view of terrorism in the world. Until then, the defense agenda in the West was the “war on drugs” policy, however after the 2001 attacks, this changed to the idea of a “war on terror”. In a natural movement, the next step meant realizing that the enemies no longer came from the Americas, rather from another continent. Countries such as Colombia that wanted North American support considered the idea of a war on drugs and a war on terror (Nascimento Júnior & Silva de Souza, 2021). This premise served to relate the financing of attacks and insurgencies that took shape from the 1980s onwards. Drug trafficking began to operate in close relation to politics and corruption, becoming the driving force behind terrorism (Bevilacqua & Villena, 2021).

Across the world, terrorism has always been dynamic in its structure, isolated or combined, born out of religious, political, ideological, and racial conflicts (Waldmann, 2005). Generally, global terror was understood as a way of attracting attention to a cause, predicted by some racial, political, or religious ideology. Very often, just as in drug producing countries, it has been associated with drug trafficking (Maleckova & Stanisic, 2011).

Hence, a modern variant known as narcoterrorism begins. Defined as violent actions against the population which aim to influence a nation’s political decisions, this has become a strategic cooperation between drug trafficking mafias and armed groups (Hermosillo, 2017).

Depending on the region, its forms vary. In Latin America, for example, drug trafficking is the major promoter of terrorist actions, especially among countries that produce cocaine. In this case, the association takes place through the fight for territories and logistic control, as in the case of “narco-terrorists” and “narco-insurgents” (Bereicoa, 2017). There are attempts, for example, to canonize narco-saints, as a way of bringing families together and legitimizing crime through religion (Iglesias, 2018). The religious culture of illicit drugs also works as a large web involving all age groups, from the most diverse social classes and geographic regions.

The idea of a narco-religion was infiltrated within the Guarani culture, a quick way to spread crime and power among Latin American peoples. There were cases of saints who needed to die to increase the narco-doctrine (but everything was just an act). This is what happened with the Michoacana family and their leader “El Más Loco” (Nazareno Moreno González) and with the cult of “San La Muerte” (Calzado, 2012). A true martyr who would be canonized and revered as a saint in every region of the continent, including in prisons (Gentile, 2007). Drug trafficking and narcoterrorism became naturally fitting parts of the grand scheme of making violence commonplace in Latin America; after all, this all contributed to a narcoculture and a narcoreligion.

In the Middle East, Asia and Africa, terrorism has taken on a different guise (Ajayi & Millard, 1997). Ideology and religion imposed other forms of violence, without the predominance of the ideal of drug trafficking logistics.

Corruption and narcoterrorism pressured political decisions and generated favoritism, were present at elections, created advantages in illicit businesses, contributed to criminal formation and fortunes, corrupted the police, and encouraged subversion and drug sales (Hilario et al., 2018).

The geographic position of a country contributes to determining the type of terrorism that will be present. Countries such as Mexico, Colombia and Peru, major producers and exporters of cocaine, have a unique type of terrorism (Cristóbal, 2018). Countries that do not produce but distribute drugs (such as Brazil) will experience other forms of violence (Mulza, 2001), as detailed below.

From 2014 onwards, when Brazil hosted major sporting events such as the World Cup and the Olympic Games, the country began to be perceived as a potential terrorist target. The presence of foreign delegations, the flow of tourists, and the high visibility profile of the events increased Brazilian vulnerability to unconventional threats (Raffagnato et al., 2019). However, cases related to terrorism continued to be investigated as other crimes or infractions, both criminal and administrative, such as the forgery of documents, dissemination of racist propaganda, and illegal entry into the country, which made it difficult to clearly identify these cases as terrorist activities. Due to the lack of current legislation, the idea that terrorism does not begin with the attack, rather with the preparations and subsequent evasion of terrorists, was ignored. (Lasmar, 2015). Nevertheless, recent events in Brazilian history have brought up the discussion: is there terrorism in Brazil, or not? This question emerged in the early years of this century.

In 2006, several drug traffickers were transferred to penitentiaries that were far apart from each other. Due to these changes, criminal groups on the Rio - São Paulo axis, commanded from within prisons, began a series of indiscriminate attacks, especially in areas with a high concentration of people, such as train, subway and bus terminals, banking establishments and universities. The legal framework did not consider such acts as terrorist (Peterke, 2007), as they did not have ideological, political, racial or religious motivations as predicted in specialized literature (Bock, 2009; Primoratz, 1990; Ruby, 2002). 59 security agents and 564 civilians were killed between May 12th and 21st that year (Amadeo, 2006). At the time, there was no direct confrontation between police forces and organized crime; it was another opportunistic and casual occurrence. The city effectively came to a stop out of fear, which is a characteristic of a certain action (Cruz, 2016).

The conflict between the criminal factions only ended when negotiations between the state government and criminal leadership reached an agreement. As a conclusion, the leadership of the attacks (Primeiro Comando da Capital) kidnapped reporter Guilherme Portanova and technical assistant Alexandre Coelho Caladopara in order to place greater emphasis on the event (Adorno & Dias, 2016). The next chapter predicted the birth of a new type of violent and armed crime: the New Cangaço.

The emergence of Novo Cangaço

In parallel to these events, a variant of terror known as the new cangaço was developing in Brazil, a term analogous to the crimes committed by criminals in northeastern Brazil who held small towns in the region hostage. The police themselves coined the term new cangaço to describe an action of terror carried out by gangs aiming to rob banks in small towns in the interior of Brazil. They chose locations that had little police force, kidnapped residents, used explosives, and planted devices that facilitated escape. The protagonists of this type of crime were specialized. There was a distribution of tasks and roles such as driver, accountant, and thief, among others. Everyone is oriented to put on a show in their practices. They also used cutting-edge technology in the robberies and a lot of prior study of routines and reaction strength. The robbers’ wide network of interpersonal relationships allowed for a broad-spectrum technical cooperation connection. These were actions committed by professional individuals. (Aquino, 2020).

Such criminals did not maintain proximity to each other, they sought to meet only to commit crimes. Their weapons were personal, each criminal had their own rifle. There was a certain hierarchy within the crimes, as theft was divided into disproportionate quantities, depending on the position held (Moura, 2022).

Table 1 shows the violence present in this type of robbery and explosion of ATMs. Over the course of 11 years, around 150 criminals were killed in clashes with the police. Some were killed in actions subsequent to the robbery, during chases and searches in hiding places.

Table 1 Fatal victims

It is important to highlight that in some cases, several criminals died in situations and periods far removed from the robberies. This was the case in Varginha (2021), when 25 criminals exchanged fire with security forces. The plan they had for new robberies was thwarted in an operation that involved the civil and military police of several Brazilian states. In this relationship (Table 1), data was related based on direct confrontation and did not consider possible deaths that occurred in situations adverse to robberies. These cases only related to crimes by the new cangaço.

Sources specializing in public security link the new cangaço to the deaths of around 170 criminals, 17 civilians and 10 security agents over a period of 20 years. These gangs affected areas with 7.6 million inhabitants in more than 20 cities from 2016 to 2022 (Filho, 2022).

In seven years, 280 cases of break-ins and ATM explosions were recorded in the state, representing an average of 40 cases annually. Following the growth trend of the previous year, gang actions reached their highest numbers in 2015 with 61 attacks. Of the

217 municipalities in the state of Maranhão, ATM break-ins and/or explosions were recorded in 134, representing 62 % of all municipalities (Sodré, 2018).

The peak of the new cangaço’s actions occurred between 2020 and 2022 with the robberies of Criciúma and Araraquara, when both cities were isolated and taken hostage by the robbers. It is of note that these were large cities by Brazilian standards (more than 220 thousand inhabitants). On this occasion, several people were used as human shields or as roadblocks, improvised explosive devices were installed on main streets, and armored vehicles were used by the gang, as well as 5.56 and 7.62 caliber rifles and .50 machine guns. At the time, it was common practice to besiege a city that would become the target of the gang’s violence. After the robbery in Criciúma, the new cangaço acted in several cities in the interior of Brazil, mainly in the state of Minas Gerais. (Lara, 2021; Matravolgyi et al., 2021).

In these episodes involving Brazilian organized crime, the organization of operations follows systematic steps, as is the case in large corporations. There is a sector in charge of logistics and food, a group that organizes the strategy for confronting police, an accounting department and, finally, another unit that organizes the escape routes. The term new cangaço was used in the media in 2021 but lost a lot of strength when 25 members of gangs specializing in bank robberies were killed in a confrontation with the police in the city of Varginha, Minas Gerais. The peak of the violence was in 2018, with 20 arrests and deaths. From 2018 onwards, this criminal practice was moving towards cybercrimes. (Barreto Filho, 2021).

These crimes has several points in common: the use of improvised explosives, such as personal traps; use of high-firepower weapons (rifles, heavy machine guns, grenades, shotguns and pistols); armored vehicles; ballistic vests; drones; and a siege operation in cities using the population as human shields. One of the group’s first actions is to attack the city’s police unit and block access for reinforcements to arrive. For effective blocking they use explosives and traps and position vehicles such as trucks on the main roads. “Miguelitos” (artifacts used to puncture tires) are thrown onto the streets and roads. The operation is commanded by members of criminal factions, who operate from within prisons. In April 2022, a discussion began to increase the penalty for crimes related to the new cangaço (Nanini, 2022). Currently, police forces are rigorously combating this violent criminal practice, as are the countermeasures adopted by banking institutions (Barreto Filho, 2021).

Bank robbers are known to have a short life span, as their actions cause the police to react harshly and they are quickly eliminated in such confrontations. As of 2022, there have been no convictions for these robbers under anti-terrorism laws.

In addition to a short life, criminals who act along the lines of the new cangaço, are not afraid of being convicted and arrested. While in prison, such a criminal continues to act as a criminal leader and coordinate robberies, drug trafficking, and enemy trials. (Moura, 2022).

Only 11 people have been convicted under the current anti-terrorism law, which saw its 6th year in 2022, a period during which a total of 6 investigations were opened. Even in the largest operations against alleged terrorists in the country, there were cases in which the courts refused the charges and suspects who, after preventative arrests, were not prosecuted (Agência Estado, 2022).

Method description

We believe that detailing the VosViewer word cluster creation technique would not contribute to the objective of this study, as numerous manuals have already been published. It is worth highlighting the work of Dutch authors Nees Jan van Eck and Ludo Waltman who wrote out the procedure in an expanded form. This manual currently has more than 33 thousand citations. For more details see Van Eck and Waltman (2014).

The organization of research planning followed the order in which references on terrorism and new cangaço were collected. In this way, two qualitative studies were created. Study 1 was a survey of approximately 14 thousand publications on terrorism and study 2 entailed interviews with experts. The process then continued in the direction of interviewing security agents from the Army and police involved with terrorism and bank robberies in Brazil.

Participants and sample

We organized data collection into two fields:

- Field study 1 – the English term “terrorism” was searched for in the Web of Science and Direct Science databases. The purpose of this procedure was to identify clusters for the word in question.

- Field study 2 – we selected 7 defense agents who were directly involved with terrorism, cybercrime and operations to combat the crime of bank robberies. Some of these professionals worked directly (field actions and investigation) in combating crimes related to the new cangaço. We conducted in-depth interviews, recordings and transcriptions.

The interviewees are public security agents in Brazil, including 2 agents from the Civil Police of the State of Goiás, 1 agent from the Federal Police, 1 agent from the Judicial Police, 1 officer from the Brazilian Army and 2 officers from the Military Police. Experience in combating organized crime was considered a prerequisite for sample selection.

Materials and equipment

Study 1 – after data collection, the database was grouped in the “.ris” format and imported into the VosViewer system. We previously used the Mendeley system to group the two databases and make it possible to extract references to support the theoretical framework.

The VosViewer program allows for the creation of color maps from survey data. It is a network viewer that uses the JAVA programming language and helps with understanding how information is connected in a visual and easy-to-understand way.

Vosviewer can be used to highlight the most influential researchers and institutions, monitor the development of research areas, measure the impact of publications, identify co-citation networks between authors, and find new areas of research. The software adopts the method known as VOS (Visualization of Similarities) to define the nodes and connections in a network. Thus, it creates visualizations in two dimensions in which objects with high similarity are closer. For example, if two researchers are located closely in the visualization and the connection between them is greater, then there is a greater tendency for them to be cited in the same publication.

Associated research is listed below, highlighting its possibility of replication.

Study 2 – interview participants were selected based on their key activity: experience with terrorism or combating bank robberies. The interview script consisted of questions such as: “what is terrorism” and “what is the new cangaço”. The interviews were recorded and later transcribed.

Data analysis technique

Study 1 – the objective of exploring the 14 thousand related articles was to identify clusters and connections between the concept of terrorism. The VosViewer system operates with distance measurements between words and their importance is also related. Links joining segments are also indicated. The scoring attributes indicate the importance of the item. An item with a greater weight is considered more important than an item with a lighter weight. When viewing a map, items with greater weight are shown more prominently than items with less weight. The distance between two items in the visualization roughly indicates the relationship of these constructs: in general, the closer two words are located, the stronger their relationship.

Associated research is listed below, highlighting its possibility of replication.

Study 2 – the interviews were grouped by participants. The 6 blocks of interviews were analyzed in light of Bardin’s theory (1977); the core words highlighted the importance of each segment. The number of times each word was said revealed the importance of each item in the general context. Data analysis for study 2 was directly influenced by the findings obtained in study 1.

Data analysis

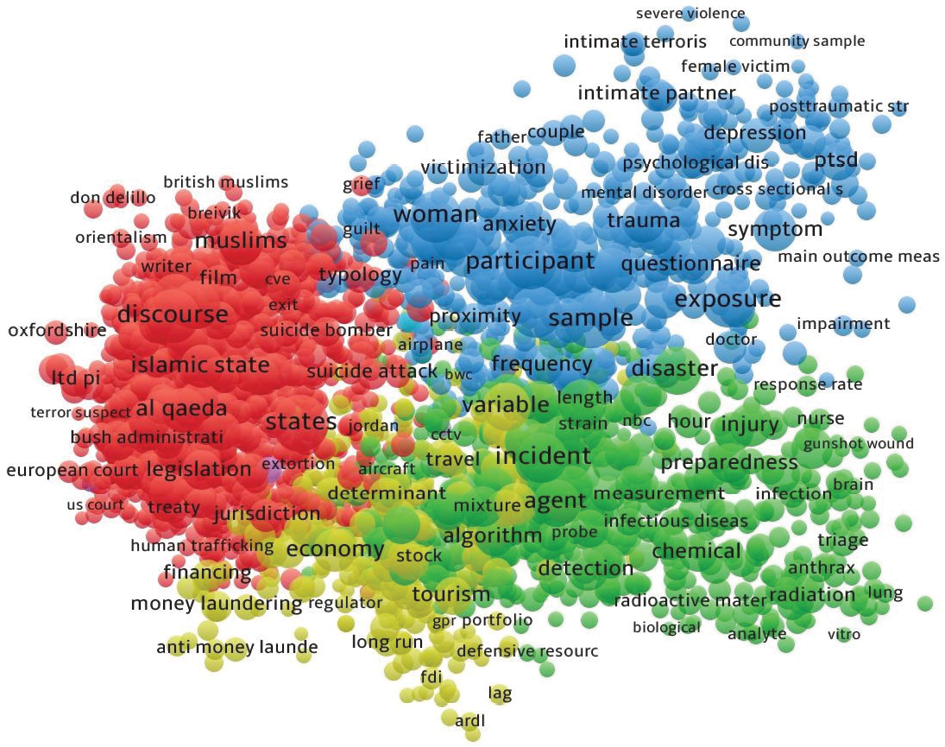

When analyzing 19 454 documents related to terrorism, observing the period from 1954 to 2022, 4 groupings emerge from the data. It appears from the documentary analysis that the terror perceived in the period from 1990 to 2020 was related to the actions of drug trafficking and bank robbery gangs. The clusters bring together specific words for these 4 clusters.

The procedure uses algorithms that group and separate similar and dissimilar words, calculating distances between them. This way, words that are related will form the same group, as is the case with tourism + money + economic. The composition of these words associated with similar ones will build the “yellow” cluster, the group that deals with the financing of terrorism. For more details on the use of the technique, we suggest consulting the article by Van Eck and Waltman (2014).

In 2022, important publications listed the paths and trends for publications on the topic of terrorism (Haghani et al., 2022). Around 18 thousand publications had been linked (in the present study we gathered 19 thousand through the Web of Science database). These publications identified clusters such as (a) political, ideological and criminological, (b) economic, (c) psychological, and (d) emergency response aspects of terrorism research. These fields were shared by this study. This research was also successful in (a) objectively determining the structural composition of the field and (b) identifying areas without adequate representation. The authors found opportunities to study the behavior of those who were involved in terrorist attacks, as well as understand the best response strategies to various forms of terrorist attacks.

In similar analyses, it was also evident that there is an opportunity for studies that could help predict terrorist actions, both with algorithms and the use of qualitative analyzes (Olabanjo et al., 2021).

Group A (red) – Al Qaeda, Islamic State, Bin Laden, bomb attacks, suicide bombings and drug trafficking and trade. This grouping contains the majority of scientific articles related to terrorism. Bomb attacks are preferred by extremist groups and a series of studies have already investigated the operations and effects of these explosive attacks (Olesen, 2011; Zgonec-Rozej, 2011).

Group B (green) – biological attacks, chemical agents, conventional warfare, nuclear energy, viruses, and bacteriological attacks. In this group, a great opportunity for studies arises, related to attacks on crops and grain production, known as agro-terrorism, when bacteriological agents can contaminate a country’s food production system. (Caldas & Perz, 2013). This group also includes examples of attacks with biological agents such as Covid-19, which can be improvised as a biological weapon. According to the authors, 33 terrorist attacks involving biological agents were registered between 1970 and 2019, registering 9 deaths and 806 injuries. 21 events took place in the United States, 3 in Kenya, 2 in the United Kingdom and Pakistan and a single event in Japan, Colombia, Israel, Russia and Tunisia (Tin et al., 2022).

Group C (blue) – collective traumas, clinical implications, stress, anxiety, psychological violence, and illnesses. Terrorist attacks mainly occur in urban centers, in regions that cause great commotion and social impact. Populous cities are those chosen for attacks and the consequences generated by these traumas are studied by medical schools and non-governmental associations (Elfversson & Höglund, 2021).

Group D (yellow) – marketing, financing, economy and tourism. This group includes peripheral systems that embrace terrorism. Countries with a greater flow of tourists and tax havens are targets for terrorist actions, whether through corruption and money laundering or due to the impact on tourists caused by attacks. Notably, cyber terrorism and cyber defense, important aspects for the digital economy, are not present in a significant way (Plotnek & Slay, 2021).

The classifications show the typification of each type of violence. Attacks carried out with explosives belong to the same group as violence committed by drug traffickers and traders. This variant of terror is not associated with the violence resulting from attacks carried out by chemical, radiological, bacteriological, and nuclear agents. The other groups deal with the sources of financing terrorism and its effects on the health of victims.

Figure 1. Cluster of violence

Group A (red) indicates the best-known type of terrorism today, that oriented towards religious, racial and political aspects, employed by extremists such as the Islamic State and Al Qaeda (Zelin, 2014; 2021). It is possible to see a connection between group D (yellow) and group A when understanding the ways of combating global terrorism, which consist of pursuing sources of income and sending resources to the origins of crime. In this group, chemical and bacteriological agents and the use of artificial intelligence to combat the actions of terrorism stand out. The green group is specific as it highlights the violence caused by the use of agents such as Anthrax (Mayer et al., 2001; Mintz et al., 2002). The intersection between the groups suggests the importance of combating the media exposure that terrorism pursues to publicize its actions, as a practice of gaining notoriety and respect (Piwko et al., 2021).

The four pillars that involve terrorist practices are foreseen in the groupings: attacks and extremist groups; ways to combat terrorism; and the consequences of terrorist actions and alternative, but no less lethal, actions of terrorism (Ganor, 2021; Ganor & Wernli, 2013).

The findings from the interviews made it possible to understand that in practice, it is only possible to classify a terrorist under current laws if there is an attack on public events or public facilities.

Therefore, the new cangaço brings together these four pillars when it is designed and composed by extremists. The gangs are specialized in just one type of crime: bank robbery; The officers involved are also experts in bank robberies and hostage-taking.

“The new cangaço cannot be considered terrorism as it is not generated by aspects of race, creed, and religion. Its results, which aim to cause disorder, panic, and insecurity in rural cities, are perceived as bank robberies and not as terrorism. Framing a bank robbery as terrorism has no legal support” (interviewee A).

If a historical search is carried out across Brazilian scientific publications, it will be possible to list the crimes related to terrorism that occurred during the military government (1964-1986). After this period, even with new patterns of poverty and the serious public security crisis, together with the growth of large cities, organized crime increased, but not to the point of being called terrorism. Criminal factions operate from within prisons, orchestrating drug trafficking, kidnappings and bank robberies, often with international connections, but are not seen as terrorists (Adorno & Salla, 2007).

For the Brazilian police, the wave of bank robberies and practices of the new cangaço can already be considered as news from the past. After all, the gangs have already been dismantled and their members have been killed by police action [...] (interviewee C).

In this interview, a police officer involved in bank robberies comments that this type of crime no longer exists. Around 30 days earlier, 25 criminals were killed in an exchange of gunfire with the police in the city of Varginha (MG); 2 days after the interview, a violent robbery took place in the city of Guarapuava (MG) with three police officers injured in the confrontation. One of the police officers died in May 2022.

In a few years, digital money will put an end to this type of crime. With the end of large volumes of money in circulation, cyber terrorism can take over the space of the new cangaço.

In the area of cybercrime investigation, we realize that all crimes have some connection with crimes committed using the internet. This was the natural migration of crimes committed on the streets. The result of this is that we need to work together with other police departments in other states, mainly for the use of wiretaps and related investigations. [...] the criminal seeks to operate in other territories, precisely to make police investigation work more difficult. Local police generally have no information about new criminals in that region (interviewee E).

In Brazil, the definition of terrorism currently leaves room for numerous interpretations. It could be something like using or storing explosives, storing toxic gases, poisons, biological, chemical, or nuclear materials, or other means capable of causing damage or promoting mass destruction.

[...] sabotage the operation or seize, with violence, a serious threat to the person or using cybernetic mechanisms, total or partial control, even if temporarily, of means of communication or transport, of ports , airports, railway or bus stations, hospitals, nursing homes, schools, sports stadiums, public facilities or places where essential public services operate, power generation or transmission facilities, military installations, oil exploration, refining and processing facilities and gas and banking institutions and their service network (interviewee A).

The legal reaction to increasing the laws that classify the new cangaço as a heinous crime has advanced. In 2022, proposal PL 610/2022 was processed in the Brazilian Senate, which includes mega-robberies of banks in acts of terrorism, with penalties of 12 to 30 years in prison. (Viana, 2022).

From this definition, it is clear that the main international legislation sought protection to frame organized crime actions. After all, these could be confused with terrorism. Consequently, terrorism is associated with ideological, political, racial, or religious reasons. Regarding the Brazilian reality, it is believed that when naming heinous crimes as terrorism, there could be difficulty in interpreting crimes classified as such without control. In particular, there was fear of the biased application of criminal penalties to social movements and protests, which often attract individuals willing to use violence and commit vandalism, but who do not have a truly terrorist profile (Peterke, 2014).

In addition to the fact that there are already sufficient laws to cover crimes of this nature, it is known that drug trafficking is closely related to this practice of violence, an old phenomenon that has been intensifying since the 1980s (Zaluar, 2004). The examples are countless and should be sought in the various rebellions that shook the penitentiary systems of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro from the beginning of the 1990s. This relationship is also seen in several Latin American countries.

[...] it is known that it is not drug traffickers who rob banks, it is not their standard action. The drug trafficker profits from the transfer of drugs and having the police around him hinders commercial practices. But it is drug trafficking that rents or sells the weapons for the robberies. Bank robbery gangs are ‘clients’ of drug traffickers (interviewee B).

Violence related to drug trafficking in Latin America must be perceived as an action of organized crime, even if orchestrated by groups confined in maximum security prisons, and not as narco terrorism. The use of the “narco” prefix for terrorism, in fact, arose due to its violent ingredients, such as attacks with improvised explosives, kidnappings, attacks on military posts, bank robbery, and guerrilla actions (Miller & Damask, 1996). Currently, Brazil finds itself helpless in the face of its laws for regulating anti-terrorism practices.

The financing of specialized crime follows the same path as terrorism. One of the reasons that led to a reduction in the crime of bank robbery was embezzlement. Scammers migrate to drug trafficking crimes. There will only be a bank robbery when organizations like the PCC need quick resources [...] it’s very risky (interviewee F).

In August 2016, Brazil hosted the Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro. With this global event and, nine months earlier, one of the worst terrorist attacks in history which killed 130 people in Paris, a discussion arose about the Brazilian anti-terrorism law. This discussion did not advance; seven years after the attack in France, this violent act would still not be considered a terrorist attack according to Brazilian law (Silva, 2019).

Starting in 2016, a discussion about how to frame terrorism in Brazilian legislation gained traction. This debate did not advance, however, and the law remained at a standstill. Issues such as financing, handling of explosives, attacks, kidnappings, and actions against the police force, triggered together, are not seen as terrorist acts [...] Marcola [PCC leader, Primeiro Comando da Capital], in 2006, took Brazil’s largest city hostage. This was terrorism (interviewee D).

Based on the law amended in 2016, setting fire to public transport or even carrying out cyber-attacks do not constitute acts of terrorism. The interpretation is that there are already laws for such crimes (Law 13.260, 2016).

For there to be a crime of terrorism, there must be a surprising criminal action from the point of view of emotional impact, with the presence of a threat to social order and peace or the imposition of a will or even coercion with institutionally established entities. Thus, the existing criminal types prove to be insufficient for combating terrorism (Buzanelli, 2013). This would offer an important explanation for Brazilian inattention to terrorism: there is no history of terrorist actions as provided for in the laws and the modalities that emerge are classified as other criminal manifestations, even if cities are surrounded and threatened for hours.

In 2018, all the ingredients for a terrorist act were gathered in the city of Ipameri, Goiás.

Around 20 criminals got together and blew up all the ATMs in the city. They took hostages using heavy weaponry and held them for 2 hours. It was the biggest action ever recorded in Goiás. They were all recidivists with a history of specialized crime and had extensive experience in bank robberies, with links to Comando Vermelho [...] in fact, it is important to emphasize that the explosion of an ATM acts as a baptism in the profession of robber. The criminal usually starts with this and then gets promoted (Moura, 2022).

The opinion of Brazilian experts from the Army and auxiliary forces such as the Military and Civil Police, who even participated in operations to combat the new cangaço, were interviewed in this research. They agreed in their belief that organized crime for bank robberies has been redirected towards embezzlement and digital crimes. They also agree that the violent operation of surrounding cities leaves a legacy of learning for other criminal practices, distinct from that of stealing cash cells from ATMs and banks.

The findings from the analysis of articles point to the issue of crime segmentation. Given the high specialization required, not just any criminal can participate in an action like those listed. It is possible that such teachings coming from the new cangaço serve as an example for other criminal factions related to drug trafficking in Latin America, since drug production and marketing networks maintains a close connection.

Conclusions

The fact that Brazil has gaps in its laws for classifying some crimes as terrorism, by default, includes the country on the list of countries that invite potential terrorists. In addition to being considered a natural corridor for the exit of drugs from South America, it also has a territorial extension that allows criminals to escape and easily leave the country across multiple borders. Brazil does not consider crimes against property to be terrorist actions. This fact also suggests a failure, this time related to the financing of terror practices. The trafficker is the one who rents weapons and sells ammunition to subsidize attacks such as those that occurred during the practices of the new cangaço.

When we investigated around 18 thousand published articles and highlighted four distinct groupings, we suggested the complexity involved in the study of terrorism. When in analyzing interviews with people who helped fight organized crime and bank robberies, we suggest that Brazilian robberies border on any practice of terror, only dominated when the new cangaceiros are killed or arrested in police action (just like Virgulino Ferreira , Lampião, the best-known cangaceiro in the country). We believe that one of the most important factors in the presence of terrorist practices in Brazil is the manufacture of explosives by criminals.

Criminal factions such as Comando Vermelho and Primeiro Comando da Capital tried to infiltrate criminals into the Brazilian political system, and this is another point that directs drug trafficking crimes and high-profile robberies towards terrorism. A link is created here that associates the new cangaço and drug trafficking with political movements.

The research findings indicate that the crime known as new cangaço was practiced sporadically in Brazil in 2022, and that the explanation for this is related to cybercrimes. It is less risky to operate over the internet and just as profitable. Furthermore, paper currency is increasingly rare in Brazil, with the advent of electronic transfers becoming more and more common.

Considering these points, we believe that the new cangaço is a form of terrorism, given its connection with drug trafficking, political movements, use of explosives, siege of cities, and use of hostages and violence aimed at causing terror and commotion. Such practices may cease to exist due to the disappearance of paper currency, but the legacy will remain and serve as a lesson for those who wish to commit similar crimes.

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest among the authors of this research. We declare that we have no financial or personal relationships that could influence the interpretation and publication of the results obtained. We also assure ensure that we always comply with ethical standards and scientific integrity at all times, in accordance with the guidelines established by the academic community and those dictated by this journal.

References

Adorno, S., & Días, C. N. (2016). Cronología dos “Ataques de 2006” e a nova configuração de poder nas prisões na última década. Revista Brasileira de Segurança Pública, 10(2), 118-132.

Adorno, S., & Salla, F. (2007). Criminalidade organizada nas prisões e os ataques do PCC. Estudos Avançados, 21(61).

Agência Estado. (2022). Apurações contra terrorismo mantêm ritmo de queda. R7. https://noticias.r7.com/brasil/apuracoes-contra-terrorismo-mantem-ritmo-de-queda-03102021

Ajayi, O., & Millard, G. H. (1997). Drugs and corruption in Latin America. Dickinson Journal of International Law, 15(3), 543-533.

Amadeo, J. (2006). Uma análise dos Crimes de Maio de 2006 na perspectiva da antropologia forense e da justiça de transição. Centro de Antropologia e Arqueologia Forense.

Aquino, J. P. D. de. (2020). Violência e performance no chamado ‘novo cangaço’: Cidades sitiadas, uso de explosivos e ataques a polícias em assaltos contra bancos no Brasil. Dilemas, Revista de Estudos de Conflito e Controle Social., 13(3), 615-643.

Barreto Filho, H. (2021). Polícia identifica suspeitos mortos em Varginha MG. UOL. https://noticias.uol.com.br/cotidiano/ultimas-noticias/2021/11/06/policia-identifica-suspeitos-mortos-varginha-mg-quem-e-quem.htm

Bereicoa, T. L. (2017). Políticas de seguridad de Estados Unidos en Perú en el siglo XXI: la configuración del “narcoterrorismo” y los “desastres naturales” como amenazas. XVII Jornadas Interescuelas y Departamento de Historia, 978-987.

Bevilacqua, S. y Villena, J. E. N. (2021). Corrupción administrativa y terrorismo: un distanciamiento considerable entre intereses y publicaciones. Gestión y Política Pública, 1(1), 20.

Bock, A. (2009). Terrorismus. UTB.

Buzanelli, M. P. (2013). Porque é necessário tipificar o crime de terrorismo no brasil. Revista Brasileira de Inteligência, 8, 9-19.

Caldas, M. M., & Perz, S. (2013). Agro-terrorism? The causes and consequences of the appearance of witch’s broom disease in cocoa plantations of southern Bahia, Brazil. Geoform, 47, 147-157.

Calzado, W. (2012). “El santo quiere fiesta”. Devoción, halagos y Agasajo a San La Muerte. Virajes Antropol. Social, 14(2).

Cristóbal, M. (2018). La amenaza del narcoterrorismo y la respuesta de los estados, un análisis comparado de la respuesta de la república del Ecuador y de la República Argentina. Revista de Ciencias de Seguridad y Defensa, III(4), 52-83.

Cruz, P. (2016). Crimes de Maio causaram 564 mortes em 2006; entenda o caso. Agência Brasil. https://agenciabrasil.ebc.com.br/direitos-humanos/noticia/2016-05/crimes-de-maio-causaram-564-mortes-em-2006-entenda-o-caso

Elfversson, E., & Höglund, K. (2021). Are armed conflicts becoming more urban? Cities, 119(1).

Liévanos, R. S. (2012). Certainty, Fairness, and Balance: State Resonance and Environmental Justice Policy Implementation 1. Sociological Forum, 27(2), 481–503. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1573-7861.2012.01327.x

Filho, H. (2022). Ações de “novo cangaço” tiveram ao menos 197 mortes, aponta levantamento. Segurança Pública, UOL. https://noticias.uol.com.br/cotidiano/ultimas-noticias/2022/06/06/acoes-novo-cangaco-mortos.htm

Ganor, B. (2021). Artificial or human: A new era of counterterrorism intelligence? Studies in Conflit & Terrorism, 44(7), 605-624. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2019.1568815

Ganor, B., & Wernli, M. H. (2013). The infiltration of terrorist organizations into the pharmaceutical industry: Hezbollah as a case study. Studies in Conflit & Terrorism, 36(9), 699-712. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2013.813244

Gentile, M. (2007). Escritura, oralidad y gráfica del itinerario de un santo popular sudamericano: San La Muerte. Espéculo: Revista de Estudios Literarios, 37(1).

Locatelli, A. (2014). What is terrorism? Concepts, definitions and classifications. In Understanding Terrorism (pp. 1-23). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Haghani, M., Kuligowski, E., Rajabifard, A., & Lentini, P. (2022). Fifty years of scholarly research on terrorism: Intellectual progression, structural composition, trends and knowledge gaps of the field. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 68(1).

Hutchinson, S., & O’malley, P. (2007). A Crime–Terror Nexus? Thinking on Some of the Links between Terrorism and Criminality 1. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 30(12), 1095–1107. https://doi.org/10.1080/10576100701670870

Hermosillo, M. Á. G. (2017). Sobre el concepto de terrorismo. Triarius, 1(16).

Hilario, M. E., Egoavil, A. S. y Porras, A. V. (2018). Breve análisis del delito de tráfico de drogas en la legislación peruana. Cuadernos Jurídicos Ius et Tribunalis, 4(4), 89–107.

Iglesias, J. M. (2018). Criminología y conducta criminal: las canonizaciones transgresoras en relación al narcoterrorismo y la delincue... Academia. Revista Latinoamericana de Administración, 3(3), 48-51.

Khan, R. M. (2024). A case for the abolition of “terrorism” and its industry. Critical Studies on Terrorism, 1-24.Lara, R. (2021, August 30). Quadrilha deixa 20 explosivos em Araçatuba e homem fica ferido ao se aproximar de bomba. CNN Brasil.

Lasmar, J. M. (2015). A legislação brasileira de combate e prevenção do terrorismo quatorze anos após 11 de Setembro: Limites, falhas e reflexões para o futuro. Revista de Sociologia e Política, 23(53), 47-70. https://doi.org/10.1590/1678-987315235304

Law 13,260, March 16, (2016). http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2015-2018/2016/lei/l13260.htm

Maleckova, J., & Stanisic, D. (2011). Public opinion and terrorist acts. European Journal Of Political Economy, 27, S107-S121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2011.04.001

Makarenko, T. (2004). The crime-terror continuum: Tracing the interplay between transnational organised crime and terrorism. Global crime, 6(1), 129-145.

Matravolgyi, Elizabeth Jucá, J., & Lara, R. (2021, August). PM: Assalto em Araçatuba tem três mortos, cinco feridos e dois presos. PM: Assalto Em Araçatuba Tem Três Mortos, Cinco Feridos e Dois Presos. https://www.cnnbrasil.com.br/nacional/pm-assalto-em-aracatuba-tem-tres-mortos-tres-feridos-e-dois-presos/

Mayer, T. A., Bersoff-Matcha, S., Murphy, C., Earls, J., Harper, S., Pauze, D., Nguyen, M., Rosenthal, J., Cerva, D., Druckenbrod, G., Hanfling, D., Fatteh, N., Napoli, A., Nayyar, A., & Berman, E. L. (2001). Clinical presentation of inhalational anthrax following bioterrorism exposure - Report of 2 surviving patients. Jama-Journal of the American Medical Association, 286(20), 2549-2553. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.286.20.2549

Merari, A. (1991). Academic research and government policy on terrorism. Terrorism and Political Violence, 3(1), 88-102. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546559108427094

Merari, A. (1993). Terrorism as a strategy of insurgency. Terrorism and Political Violence, 5(4), 213–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546559308427227

Merari, A. (1994). Characteristics of terrorism, guerilla, and conventional war as modes of violent struggle. Encyclopedia of Human Behaviour, 4(1), 401.

Miller, A., & Damask, N. (1996). The dual myths of “narco-terrorism”: How myths drive policy. Terrorism and Political Violence, 8, 114-131.

Mintz, Y., Shapira, S. C., Pikarsky, A. J., Goitein, D., Gertcenchtein, I., Mor-Yosef, S., & Rivkind, A. I. (2002). The experience of one institution dealing with terror: The El Aqsa Intifada riots. Israel Medical Association Journal, 4(7), 554-556.

Moura, S. P. (2022). Assalto a Banco. Contexto

Mulza, G. E. M. (2001). Relações internacionais EUA-Colômbia: O caso do Plan Colômbia. Sem Aspas, 0(00), 1-13.

Nanini, L. (2022). “O Estado não pode permitir”, diz ministro da Justiça sobre o “novo cangaço.” R7. https://noticias.r7.com/brasilia/o-estado-nao-pode-permitir-diz-ministro-da-justica-sobre-o-novo-cangaco-18042022

Nascimento Júnior, W. y Silva de Souza, R. C. (2021). Narcoterrorismo e Neoliberalismo: Condicionamentos e (Re) enquadramentos do Conflito Social Colombiano [Narcoterrorismo y Neoliberalismo: Condicionamientos y (Re) encuadramientos del Conflicto Social Colombiano]. Relaciones Internacionales, 30(61), 138.

Olabanjo, O. A., Aribisala, B. S., Mazzara, M., & Wusu, A. S. (2021). An ensemble machine learning model for the prediction of danger zones: Towards a global counter-terrorism. Soft Computing Letters, 3(1).

Olesen, T. (2011). Transnational injustice symbols and communities: The case of Al-Qaeda and the Guantanamo Bay detention camp. Currenty Sociology, 59(6), 717-734. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392111419757

Peterke, S. (2007). Brasiliens Herausforderung durch den Terror der Organisierten Krimi- nalität: Nach der Anschlagsserie von Rio: Kampf dem Narcoterrorismus? Verfassung Und Recht in Übersee, 40(2), 230-248.

Peterke, S. (2014). Obrigações internacionais para criminalização do terrorismo e modelos de implementação Principais opções para o legislador brasileiro. Revista de Informação Legislativa, 204, 109-119.

Piwko, A., Sawicka, Z., & Adamski, A. (2021). Terrorism, Politics, Religion Challenges for neus Media in the Middle. European Journal of Science and Theology, 17(3), 11-25.

Plotnek, J. J., & Slay, J. (2021). Cyber terrorism: A homogenized taxonomy and definition. Computers & Security, 102(1).

Primoratz, I. (1990). What is terrorism? Journal of Applied Philosophy, 7(2), 129-138.

Raffagnato, C. G., Abdalla, T., Cardoso, D. O. y Fontes, F. D. V. (2019). Terrorismo químico: Proposta de modelagem de risco envolvendo ricina em eventos de grande visibilidade no Brasil. Saúde Debate, 43(3), 152-164. https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-11042019S311

Ruby, C. L. (2002). The definition of terrorism. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 2(1), 9-14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-2415.2002.00021.x

Schmid, A. P. (2011). The Routledge Handbook of Terrorism Research. Routledge.

Silva, A. (2019). 7 motivos para o Brasil aprovar com urgência a Lei de Combate ao Terrorismo. Associação Dos Procuradores Da República. https://www.anpr.org.br/artigos/7-motivos-para-o-brasil-aprovar-com-urgencia-a-lei-de-combate-ao-terrorismo

Sodré, R. B. (2018). O novo cangaço no Maranhão. Confins, 37. https://doi.org/10.4000/confins.15811

Suarez, M. A. G. (2012). Terrorismo e política internacional : Uma aproximação à América do Sul. Contexto Internacional, 34(2), 363-396.

Tin, D., Sabeti, P., & Ciottone, G. R. (2022). Bioterrorism: An analysis of biological agents used in terrorist events. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 54(1), 117-121.

Van Eck, N. J., & Waltman, L. (2014). Visualizing bibliometric networks. In Measuring scholarly impact: Methods and practice (pp. 285-320). Springer International Publishing.

Van Eck, N. J., & Waltman, L. (2014). CitNetExplorer: A new software tool for analyzing and visualizing citation networks. Journal of informetrics, 8(4), 802-823.

Van Eck, N. J., Waltman, L., Dekker, R., & Van Den Berg, J. (2010). A comparison of two techniques for bibliometric mapping: Multidimensional scaling and VOS. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 61(12), 2405-2416.

Venkatachary, S. K., Prasad, J., Alagappan, A., Andrews, L. J. B., Raj, R. A., & Duraisamy, S. (2024). Cybersecurity and Cyber-terrorism Challenges to Energy-Related Infrastructures-Cybersecurity Frameworks and Economics–Comprehensive review. International Journal of Critical Infrastructure Protection, 100677.

Viana, S. C. V. (MDB/MG). (2022). senado.leg.br. Plenário Do Senado Federal (Secretaria Legislativa Do Senado Federal). https://www25.senado.leg.br/web/atividade/materias/-/materia/152221

Waldmann, P. (2005). Provaktion der Macht (2nd ed.). Murmann Verlag.

Waltman, L., Van Eck, N. J., & Noyons, E. C. (2010). A unified approach to mapping and clustering of bibliometric networks. Journal of informetrics, 4(4), 629-635.

Waltman, L., & van Eck, N. J. (2013). Source normalized indicators of citation impact: An overview of different approaches and an empirical comparison. Scientometrics, 96, 699-716.

Zaluar, A. (2004). Integração perversa: pobreza e tráfico de drogas. FGV.

Zelin, A. (2014). The War Between ISIS and al-Qaeda for Supremacy of the Global Jihadist Movement. Washington Institute for Near East Policy, June 2014(20), 11.

Zelin, A. (2021). The Case of Jihadology and the Securitization of Academia. Terrorism And Political Violence, 33(2), 225-241. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2021.1880191

Zgonec-Rozej, M. (2011). Her Majesty’s Treasury V. Mohammed Jabar Ahmed and others; her majesty’s treasury v. Mohammed al-Ghabra; R (on the application of hani el sayed Sabaei Youssef) V. her Majesty’s Treasury. American Journal of International Law, 105(1), 114-121.