Introduction

The category of ‘economic crime’ is hard to define, and its exact conceptualisation remains a challenge (UNODC, 2005). Defining ‘crime’ is inherently difficult, and this challenge naturally extends to defining ‘economic crime.’ This question is closely related to a fundamental issue in criminology: whether to use a strict legal interpretation of the term “crime” or whether it is reasonable to adopt a broader, social-scientific, and political perspective (Larsson, 2001, p. 121).

Arguing that economic crime is a relatively loose term, covering a wide variety of phenomena, Tupman (2015) emphasises that the concept of ‘economic’ is also quite problematic, leading to several emerging questions.

At the 11th UN Crime Congress, the UNODC (2005) adopted a fairly protean view: “’Economic and financial crime’ refers broadly to any non-violent crime that results in a financial loss. These crimes thus comprise a broad range of illegal activities, including fraud, tax evasion and money laundering” (Levi, 2015, p. 28). Svensson (1984) defines economic crime as a crime that covers the following: a) a punishable act, b) a continuous and systematic act, c) committed for the purpose of gain and d) within the framework of a legal trade constituting the actual basis for the act.

Passas (2017) states that economic crime includes state crime, corporate and individual white-collar crime, as well as illegal enterprises, popularly called ‘organized crime.’ Amara and Khlif (2018) highlight that financial crime is a significant problem that affects both developed and developing countries, hindering social and economic progress, particularly in developing and transitional economies. Furthermore, they found that the level of financial crime is positively associated with the level of tax evasion. Therefore, analysing the economic consequences of financial crime is vital for governments to recognise its substantial costs (Amara & Khlif, 2018). Specifically, understanding its impact on tax evasion is essential for governments seeking to effectively address and combat tax evasion practices (Amara & Khlif, 2018).

Tax evasion is classified as a white-collar crime. The concept of white-collar crime was introduced by Edwin Sutherland (1945-1983), who is widely identified as the single most important and influential criminologist of the twentieth century (Friedrichs et al., 2017). At the American Sociological Association meeting in 1939, Sutherland pointed out the phenomenon of lawbreaking by “respectable” persons in the upper reaches of society (Reurink, 2016). Previous crime theories stated that only poor individuals commit crimes. However, Sutherland challenged this theory and found that rich people are commonly involved in criminal behaviour. Many corporate crime cases emerged in the 20th Century and the 21st century (Enron, WorldCom, etc.). Also, the federal government started to fund research on white-collar crime (Simpson & Weisburd, 2009), and those researchers found that economic crime relies upon more sophisticated techniques in the 21st Century. Those techniques differ from typical property and violent street crimes (Benson et al., 2009).

Economic crime consists of the following components (Hirschi & Gottfredson, 1987): self-interest crime (forces of fraud are used to satisfy personal interest), gaining immediate pleasure when committing a crime (rapidity in enhancing pleasure for the perpetrator), and it is not resource consuming for the perpetrator (using minimal effort to obtain a certain outcome). These components are also used in the legal definition of an economic crime in Serbia. Economic crime consists of actus rea and mens rea components. Actus rea is the guilty act, while mens rea consists of the mental components of the crime, and those two components are the same regardless of the gender committing the specific crime. Actus reas, according to Benson, Madensen and Eck (2009), include the business or organisation the perpetrator works within (or the fictitious business they have created) and any other outside agency, organisation, groups of clientele served, or other departments within their own organisation that they interact with to accomplish their objectives.

For the purpose of this research, we used the strict legal interpretations of the terms “crime” and “economic crime.”

In Serbia, the legal aspects of economic crimes are regulated by the Criminal Code of the Republic of Serbia. All these criminal acts are entitled as Offences against economic interests (Criminal Code, par. 22, Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia No. 85/2005, 88/2005, 107/2005 - 72/2009, 111/2009, 121/2012, 104/2013, 108/2014, 94/2016 and 35/2019). Offenses against economic interests, as a general term in the Serbian Criminal Code, cover many offenses. However, all of them correlate with the business entity and could also be connected to the abovementioned property of white-collar crime. Tax avoidance has also been part of economic crime included in Chapter 22 of the Serbian Criminal code and described in Article 225, which focuses on “actus reas” (fully or partially avoiding payment of taxes, contributions, or statutory dues or giving false information, failing to report earnings or conceals information pertaining to the determination of tax liability) and “men’s rea” (described as intent to commit the crime).

Studies on economic crime in Serbia (Božić et al., 2016; Gavrilović, 1970; Jugović et al., 2008; Knežević et al., 2020; Kulić & Milošević, 2010, 2011; Kulić et al., 2011; Mitrović, 2006; Simović et al., 2017) are not rare, but gender gap crime research is (Dimovski, 2023), and this study could fill the research gap that exists. In this article, we try to understand the percentage of women involved in economic crime and tax fraud in Serbia, whether they are more prosecuted and reported for those offenses, and how efficient the legal system is when it comes to women accused of economic and tax fraud.

The aim of our research is to provide the government with some orientation by reviewing the literature on economic crime and tax fraud from the gender perspective and legal perspectives. The goal is to make recommendations and establish preventive measures for women to avoid this crime.

Literature review

Most criminological theories are rooted in one or two academic disciplines, making them disciplinary or, at best, multidisciplinary (Robinson, 2006). However, discussing criminological theories is quite challenging since the term “theory” holds different meanings for contemporary criminologists. This variation depends on their philosophical perspectives regarding the nature of criminology, its goals, and their views on how criminology ought to be addressed (Tittle, 2016).

Based on case histories and criminal statistics showing unequivocally that crime, as popularly conceived and officially measured, has a high incidence in the lower class and a low incidence in the upper class, scholars have developed general theories of crime that suggest that crimes are primarily caused by poverty or by personal and social traits statistically linked to poverty, including feeblemindedness, psychopathic deviations, slum neighbourhoods, and “deteriorated” families (Sutherland, 1940).

Sutherland (1940) argues that crime is not closely linked to poverty or the psychopathic and sociopathic conditions often associated with it. He suggests that conventional explanations of crime are largely flawed because they are based on biased samples that do not encompass the wide range of criminal behaviour exhibited by individuals outside of the lower class (Sutherland 1940).

He introduced the concept of “white-collar crime” to express criminality in business as misrepresentation in financial statements, manipulation in the stock exchange, commercial bribery, and bribery of public officials directly or indirectly in order to secure favourable contracts and legislation, misrepresentation in advertising and salesmanship, embezzlement and misapplication of funds, short weights and measures and misgrading of commodities, tax frauds, misapplication of funds in receiverships and bankruptcies (Sutherland 1940).

In 1947, Sutherland redeveloped his theory and emphasised the learning process only. “A person becomes delinquent because of an excess of definitions favourable to violation of law over definitions unfavourable to violation of law” (Sutherland, 1947).

The “white-collar crime” concept, referring to lawbreaking by “respectable” individuals in higher societal tiers, has migrated from academia to public discourse (Reurink, 2016). Many scholars differentiate between occupational and corporate white-collar crimes based on who benefits—the individual or the organisation. This distinction is grounded in the belief that crimes within organisations are influenced more by their goals, structures, and dynamics than by the personal traits of the offenders (Reurink, 2016). Sutherland theorised that criminal behaviour was learned from others rather than an inherent trait or characteristic of certain types of individuals (Tickner & Button, 2021). The main problem with this theory is that it has not been fully tested, so there is a lack of empirical findings supporting it. However, besides its vague context, Sutherland’s theory has influenced many researchers trying to find a way to define, measure, and test all of the factors that influence criminal behaviour (Matsueda, 2001; Opp, 1974).

Today, crime and white-collar crime are defined from different perspectives (Le Maux & Smaili, 2023), and some scholars argue that it can sometimes be difficult to distinguish between white-collar and organised crime (Albanese, 2021).

Cressey, who earned his PhD under Sutherland’s tutelage and was naturally influenced by Sutherland’s differential association theory, developed a more complex theory of embezzlers (1953) founded on the hypothesis today known as Cressey’s fraud triangle (Tickner & Button, 2021). Cressey’s theory is considered the most traditional theory for detecting fraud today (Saluja et al., 2022).

Cressey (2017) noted that since corporations cannot have intentions, their criminal actions cannot be explained using behavioural theory. Recognising that corporate and organisational crimes are essentially phantom phenomena should not diminish criminological concern for white-collar offenses and offenders but should instead shift the focus to the real individuals within corporations and organisations who possess the psychological capacity to intend criminal acts (Cressey, 2017).

Of most relevance to criminological theory about crime causation were admonitions based on the assumption that the corporation is a person who, like other persons, has obligations under a social contract. “The theory poverty causes crime“ is applicable to corporate crime as well and explains that when organisations face difficulty in meeting their profit goals, they resort to crime (Cressey, 2017).

Strain theories, stating that certain strains or stressors increase the likelihood of crime (Agnew & Brezina, 2010), were developed to explain what was thought to be the much higher rate of crime among lower-class individuals (Agnew et al., 2009). “Strain” refers to the tension individuals feel when pursuing economic success conflicts with the legitimate opportunities available to achieve this goal (Ji et al., 2019).

There are several versions of strain theory. Classic strain theories were proposed by Merton (1938), Cohen (1955), and Cloward and Ohlin (1960). These theories dominated criminology during the 1950s and 1960s (Agnew & Brezina, 2010). Traditional strain theories are considered macro-level theories. Melis-Rivera and Piñones-Rivera (2023) highlight the dissemination and importance of identity perspective between the 1950s and 1970s and the subsequent criticism that it was reductionist, lacking theoretical support, and not in dialogue with other criminological proposals.

To address the inconsistencies plaguing traditional strain theories, Agnew and White (1992) revised them and introduced the general strain theory (Broidi, 2001), which became the leading version of strain theory (Agnew, 2015). The primary focus of classic strain theory was on monetary success rather than educational attainment or occupational status, making it inadequate for explaining criminal or delinquent behaviour (Agnew & Brezina, 2010). According to the classic strain theories, individuals from all social classes are encouraged to pursue the goal of monetary success or middleclass status (Agnew et al., 2009).

General strain theory provides a theoretical guide to understand the implications and negative consequences of officer stress/strain, which is perhaps more important to criminologists (DeLisi, 2011).

Agnew argues that strain triggers criminal responses when negative emotions, especially anger, are present and legitimate coping strategies are lacking, and this effect is heightened in social environments that promote illegitimate outcomes (Broidi, 2001).

In contrast to control and learning theories, Agnew and White’s (1992) GST provides a unique explanation of crime and delinquency by focusing explicitly on others’ negative treatment, and this is the only major theory of crime and delinquency that highlights the role of negative emotions in the aetiology of offending (Brezina, 2017). According to this theory, individuals who experience strain or stress often become upset and sometimes cope by means of crime (Agnew & Brezina, 2019).

General strain theory predicts that several variables influence or condition the effect of strains on crime (Agnew, 2013). Numerous research projects have applied the general strain theory of crime and delinquency in different areas and for different purposes (Agnew & White, 1992; Al-Badayneh et al., 2024; Baumann & Friehe, 2015; Chan, 2023; Golladay & Snyder, 2023; Huang et al., 2024; Isom et al., 2021; Kabiri et al., 2024; Khan et al., 2023; Kim et al., 2023; Kondrat & Connolly, 2023; Lee, 2024; Man & Cheung, 2022; Morgan et al., 2024; Scaptura et al., 2024; Zavala et al., 2024).

Studies on the effects of several variables that influence or condition the effect of strains on crime have produced mixed results. It is argued that certain factors must converge before criminal coping is likely: individuals must (a) possess a set of characteristics that together create a strong propensity for criminal coping, (b) experience criminogenic strains, which are perceived as unjust and high in magnitude; and (c) be in circumstances conducive to criminal coping (Agnew, 2013).

Both the classic and general strain theory argue that poorer individuals are more likely to experience certain strains or stressors (Agnew, 2015). That is why some scholars consider the existence of white-collar crime as evidence against strain theory. In contrast, Agnew et al. (2009) state that the strain theory is quite relevant to explaining white-collar crime. The GST incorporates the arguments of the classic strain theory and provides a vehicle for systematically describing the central themes in the research on strain and white-collar crimes (Agnew et al., 2009). Agnew (2015) states that the very poor are generally more likely to engage in street crime and the rich in corporate and state crime and highlights that the strain theory can better explain the mixed data on economic status and crime. Still, organisational corruption imposes a steep cost on society, easily dwarfing that of street crime (Ashforth & Anand, 2003).

Despite the Integrated Systems Theory (IST), which provides a highly positivistic account of the causes of crime in a way that challenges the notions of free will, choice and, ultimately, personal responsibility, having received little attention in criminology, several scholars consider it as the most ambitious effort yet for elevating the integration of criminological theory (Robinson, 2014).

Life course theories resolve the gender aspect of offending the law. These theories have the following aspects: criminal behaviour is not learned in childhood and depends on environmental interactions. DeLisi and Vaughn (2016) pointed out that engaging in criminal behaviour is not limited to certain social strata and that sex represents the most powerful predictor of criminal behaviour because males usually commit crimes, and sex chromosomes create genetic sex differences (Eme, 2007). Genetic, neuropsychological, neurochemical, psychophysiological, hormonal, and obstetric factors influence antisocial behaviour.

According to tax fraud criminality, the positive theory of tax evasion attempts to explain it. When individuals consider the idea of evading taxes, they decide based on the chance of getting caught and being penalised for the crime. The normative questions raised by tax evasion are often complex, involving issues of fairness, efficiency, and how to measure social costs and benefits (Slemrod, 2007). According to Slemrod (2007), tax evasion is a high-risk decision in which individuals maximise their utility by considering legal penalties for the crime. Feld and Frey (2002) found that a neglected aspect of tax compliance is the interaction of taxpayers and tax authorities. The relationship between the two actors can be understood as an implicit or “psychological” contract. They founded the so-called behavioural theory in tax fraud (Slemrod, 2007).

The criminality of women has long been a neglected subject area of criminology (Klein, 1973). Daly and Chesney-Lind (1988) state that it is common for crime theories to be developed and tested using male-only samples without any reflection on whether concepts or results may be gender-specific. Many explanations have been advanced for this, such as women’s low official rate of crime and delinquency and the preponderance of male theorists in the field (Klein, 1973).

It has long been argued that economic crime is related to masculine identity. The unemployment crime thesis is a popular explanation of male working-class economic crime (Willott & Griffin, 1999). Willott and Griffin (1999) stated that one possible account of the relationship between gender and economic crime is that it is co-mediated by masculine identity and unemployment. However, Wallace and Pahl (1986) found that unemployed people had relatively little access to the informal economy compared to those in legal employment. (Willott & Griffin, 1999). Steffensmeier et al. (2013) highlight that women’s advancement into the labour market and upward mobility have considerably reduced or eliminated gender differences in white-collar and corporate criminality.

All the theories mentioned above reflect that women’s inclusion in economic and tax crimes is a complex issue. According to Sautherlands’ theory, criminal behaviour could be learned by having contact with other perpetrators in company crime networks, or tax crime is committed when the chances of getting caught are low, as explained by the positive theory of tax fraud. In other cases, genetic, neuropsychological, hormonal, and other factors influence women’s criminal behaviour. Various factors are in play when researching women’s economic criminality, so research is usually done in a vague environment. From the standpoint of the strain theory, perpetrators, regardless of sex, commit crimes when they are poor or not included in positions of power. Davies’s (2003) empirical evidence regarding female offending styles, suggests that sex is a key variable contributing to law-breaking behaviour and could be seen as a contribution to the general strain theory. However, caution in conclusions is needed since numerous gender and age stereotypes are present not only among the population but among scholars as well (Pavlović et al., 2022).

De Lisi and Vaughn (2016) state that there has been a failure in deviance theorising about crime in this century. They explained that males display higher levels of problem behaviours than females, and that is why they are more reported as crime offenders. So, basing theories on criminal behaviour and not focusing on the sex aspect is a major obstacle in theorising about crime.

Hindelang (1979) found that there are genetic sex differences that manifest in more males reported than females. Hindelang (1979) continues with the argument about sex bias, which more often emphasises the system. The system is biased not against men but in favour of women. Willott and Griffin (1999) found that in mainstream criminology, there are no adequate explanations for why males are the most convicted individuals for crime and pointed out that theories in which those having less power commit crimes are not in line with the real fact that women usually have less power, but rarely commit a crime and show offending behaviour.

Klenowski et al. (2011) analysed the motivational aspects of individuals committing a crime and how those motives and rationalities differ among men and women white-collar offenders. The most extensive research about gender and varieties of white-collar crime is done by Daly (1989), which shows that a minority of men but only a handful of women fit the image of a highly placed white-collar offender. Men worked in organised crime groups and used organisational resources to carry out criminal acts, while women offenders were nonwhite, clerical workers with less financial net worth than male offenders.

In Serbia, only several researchers analysed economic criminality in general (Božić et al., 2016). This analysis has been done from the point of view of the Criminal law itself, describing the criminal act or lack of adequate competence of special departments for corruption, which is correlated with the suppression of corruption, which is in line with tax evasion. Simović et al. (2017) found that many perpetrators of these crimes are finally punished with mild measures and types of sentences if convicted. Knežević et al. (2020) found that the number of individuals prosecuted for tax evasion in 2014 contributed to 28.67 % of total prosecuted economic crime acts, then rose to 57.45 % in 2018. Tax crime is among the two most common types of economic crime committed in Serbia.

Scholars rarely study gender aspects of women’s criminal behaviour in Serbia, and most of the research is novel and contemporary (Dimovski, 2023; Pavićević & Bulatović et al., 2018; Pavićević, 2020). It does seem that the topic did not attract much attention because women commit less economic crime than men because of their deprivation from positions with economic power in companies. Results of Dimovski (2023) show that economic crime was in third or fourth place of all crimes committed in Serbia (region of Nis) by women in the period 2016-2020 and shows that in most cases, 91 % of women committed an economic crime as a single offender while 8 % committed this crime in cooperation with other perpetrators.

The Balkan region countries where Serbia is included share the same development in terms of being formed after a single country (Former Yugoslavia) had been dissolved. That is why comparative results could provide additional insight into the topic. In Croatia and Montenegro, which are Balkan region countries taken into consideration, studies about women’s criminality are also quite rare (Kalac & Bezić, 2023; Jovanović et al., 2023). In Montenegro, female criminality is influenced by socioeconomic, cultural, geostrategic, biological, psychological, and situational factors (Jovanović et al., 2023), with the social exclusion of women being the most dominant one. In Montenegro, the most dominant crime committed by women is crime against property, followed by crime against public safety. Only 10.28 % of women in the 5-year period committed a crime by abusing the position of power and trust, while 6.27 % of women were convicted for crimes against payment operations and business operations in Montenegro (Jovanović et al., 2023), which are economic crimes. Kalac and Bezić (2023) pointed out that the most frequent groups of criminal offenses for which females are reported in Croatia cover property offenses (mainly larceny and aggravated larceny), followed by the ‘verbal crime’ of threat. Among economic criminal acts, the results show that the number of reported females increased slightly from 2014 to 2016, and then there was a decrease from 2016 to 2019. Significant conceptual changes in the normative framework regarding economic crimes can explain the peak in 2016. The female share in economic criminal offenses is 18 %, while the share of the same gender group in financial misdemeanors is 25 % in Croatia (Kalac & Bezić, 2023).

Research questions

One of the main points in the paper is based on the theoretical proposition that more men commit all types of crime than women, and this applies to economic crime and tax evasion as well.

Research questions derived from the literature mentioned above are as follows:

RQ 1: Women are reported, prosecuted, and convicted less than men for economic crime offenses in Serbia.

RQ2: Because of the complex nature of tax fraud, women are less involved in this type of crime in Serbia.

These research questions are answered by providing general statistics on the economic crime committed in Serbia from 2014 to 2021 and specific statistics on the number of women committing economic crime offenses for the same period. Then, we extracted tax crime as the most common form of crime committed among economic offenses and analysed the number of women committing tax fraud and criminal sanctions imposed on convicted perpetrators.

Data and methodology

Measuring economic crime and tax evasion as the most important criminal act in Serbia could be done by two methods (Argentiero et al., 2020): enforcement reports and survey data based on victim studies. The first method is used by various governmental bodies such as Eurostat for European economic crime and the Serbian Bureau of Statistics for measuring the economic crime conducted in Serbia. Both methods lack reliability and suffer from methodological issues. Although the first method is more reliable, problems lie with a methodology for reporting economic and tax crime that varies among jurisdictions. That is why our paper solely focuses on one jurisdiction, Serbia.

Data has been gathered through the Serbian Bureau of Statistics and its Bulletin of adult criminal offenders in the Republic of Serbia for individual years, starting from 2014 and ending with the bulletin covering 2021. The methodology consists of secondary data used and analysed using descriptive statistics. Other researchers also apply the same methods (Božić et al., 2016; Simović et al., 2017). What we add to the statistics is the gender aspect of crime and explanations for the results given from this perspective.

Results

Descriptive statistics of economic crime in Serbia and women perpetrators

Results are given in several Tables for the period 2014-2021. Table 1 shows economic crime comprising different types of crime, including tax crime, and Table 2 shows results for the economic crime committed by women perpetrators. Table 4 shows differences between all persons reported and prosecuted and prosecuted and convicted. These numbers should give us a perspective on the efficacy of prosecution and the legal system in Serbia when fighting against these types of criminal activities. All of the differences are then tested by the Chi-Square test (Tables 2 and Table 5).

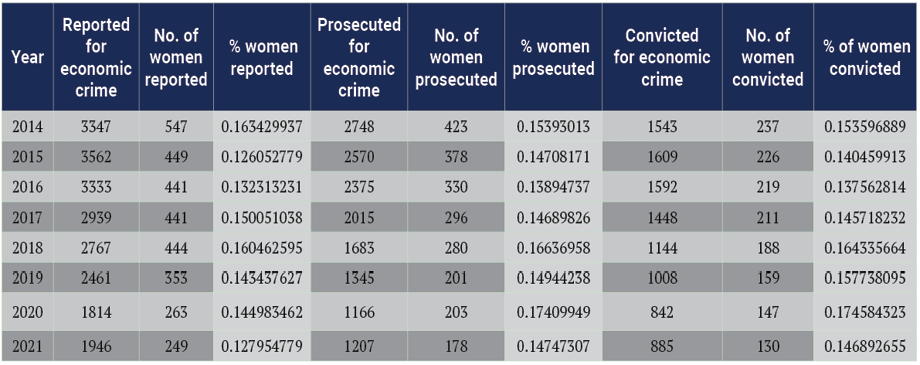

Table 1. Economic crime in terms of reported, prosecuted, and convicted individuals in the period 2014-2021 in Serbia

Source: Bulletin of adult criminal offenders in the Republic of Serbia, Serbian Bureau of Statistics.

The absolute difference between reported and prosecuted was 1116 in 2019, and the lowest was 599 in 2014. The absolute difference between prosecuted and convicted individuals was 1205 in 2014, and the lowest was 322 in 2021.

After COVID-19 in 2020 and 2021, the difference (reported -prosecuted) rose from 648 to 739. After COVID-19 in 2020 and 2021, the difference (prosecuted-convicted) decreased from 324 to 322.

The main question is why the difference between reported and prosecuted persons is always so huge. When we consider the % difference, the trend is even more visible: 45 % (2019) and 17.8 % (2014). The reason lies in the criminal procedure that leads to dropping the criminal charges because there is not enough evidence, mistakes occur at the beginning of the procedure of collecting evidence, or there is a wrong qualification for the crime. The % difference between prosecuted and convicted individuals decreased from 43.8 % (2014) to 26.6 % (2021). This means that more individuals are convicted for the crime, showing that when there is enough evidence against the perpetrators, the court decides to sanction those behaviours, and court proceedings become more efficient.

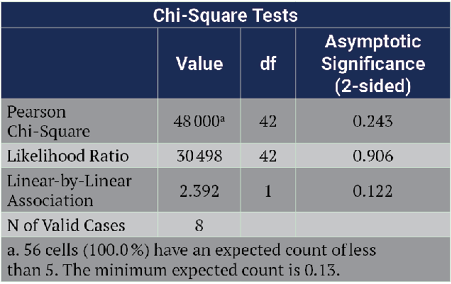

Table 2. Chi-Square test results for the difference between reported and prosecuted and prosecuted and convicted persons of both sex in Serbia

Table 2 shows that the Chi-Square is 56, and the degrees of freedom are 49. We cannot conclusively accept or reject the null hypothesis, but those differences have no correlative relationship.

The next two Tables show the number of women reported, prosecuted and convicted for economic crime and the differences between those variables for the women perpetrators.

Table 3. Economic crime in terms of reported, prosecuted, and convicted women in the period 2014-2021 in Serbia

Source: Bulletin of adult criminal offenders in the Republic of Serbia, Serbian Bureau of Statistics.

The percentage of women reported for economic crime was approximately 16.3 % in the year 2014, and then it decreased to 12.7 % in the year 2021. Fewer women after COVID-19 are reported for economic crime. In the group of prosecuted individuals for economic crime, women comprised 15.3 % in 2014 and 14.7 % in 2021. However, what seems so interesting is that in 2020, 17.4 % of women were prosecuted for economic crime, which is the highest percentage in the period mentioned above 2014-2021. Among those convicted for economic crimes, we found 15.3 % of them to be women in 2014 and 14.6 % in 2021. Also, after COVID-19 (The year 2021), fewer women were convicted for economic crimes. However, the same trend exists in 2020 when 17.4 % of all women were convicted for a crime, which is the highest percentage in the period in question.

Table 4. Differences between the number of reported and prosecuted women and the number of prosecuted and convicted women in the period 2014-2021 for economic crime in Serbia

Table 4 shows large differences between reported and prosecuted women in the years 2017, 2018 and 2019. After that, the difference is around 60 - 70. This means that more women reported are also prosecuted for economic crime acts. Table 4 also shows the largest differences between 2014, 2015 and 2016. Then the difference is lower, around 40 to 50 women. It shows better efficacy of the legal system and prosecutors in terms of gathering adequate evidence that led to the conviction of prosecuted women.

Table 5. Chi-Square test results for the difference between reported and prosecuted and prosecuted and convicted women for economic criminality in Serbia

The Chi-Square for the differences between reported and prosecuted and prosecuted and convicted women is smaller than for all sex cases: 48, with the degree of freedom being 42. We cannot conclude with certainty that we can accept or reject the null hypothesis. But there is no corelative relationship between those differences.

Descriptive statistics of tax evasion in Serbia and women perpetrators

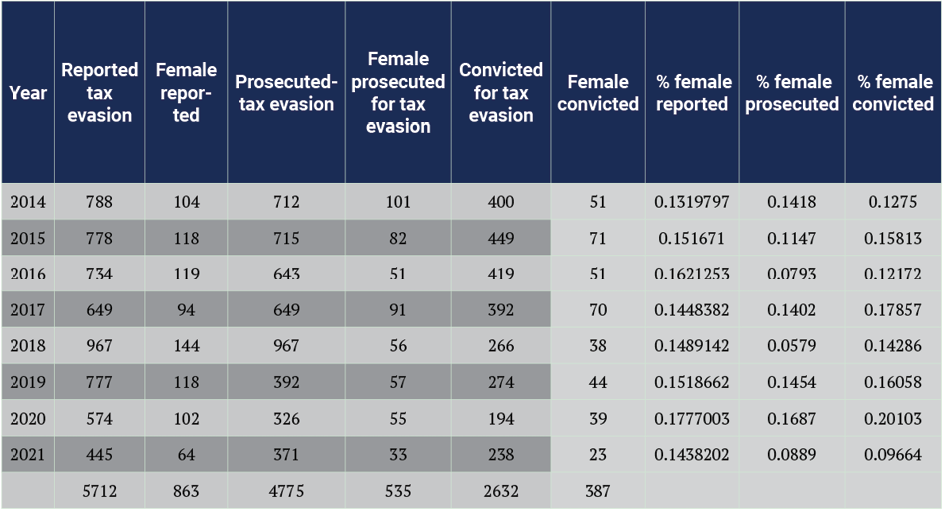

Two Tables give results for the period 2014-2021. Table 6 shows tax crimes committed by women perpetrators categorised into reported, prosecuted, and convicted. Table 7 presents differences between women reported and prosecuted and women prosecuted and convicted for tax fraud. The Chi-Square test in Table 8 tests the significance of the differences. Table 9 represents criminal sanctions imposed on all convicted groups.

In 2014, the percentage of women reported for tax crimes was approximately 13.1 %. This figure increased to 14.3 % by 2021. After COVID-19, fewer women were reported for tax crimes overall. Notably, the highest percentage of women reported for tax crimes occurred in 2020, reaching 17.7 %. Among those prosecuted for tax crimes, women made up 14.1 % in 2014 but dropped to 8.8 % in 2021.

Table 6. Tax crime in terms of reported, prosecuted, and convicted women in the period 2014-2021 in Serbia

Source: Bulletin of adult criminal offenders in the Republic of Serbia, Serbian Bureau of Statistics.

After COVID-19 in 2021, fewer women were prosecuted for tax crimes. Interestingly, in 2020, the percentage of women prosecuted for tax crimes reached 16.8 %, the highest figure recorded from 2014 to 2021. That year also saw the largest number of women prosecuted and convicted for tax crimes.

In 2014, 12.7 % of women were convicted of tax crimes, which decreased to 9.6 % by 2021. Following the COVID-19 pandemic, fewer women faced convictions for tax crimes. However, a notable trend emerged in 2020, when 20.1 % of all women were convicted of a crime, marking the highest percentage during the period under review.

These percentages are much lower than those reported, prosecuted, and convicted for economic crimes by women. It appears that women are more inclined to commit economic crimes compared to other types of financial offenses.

Table 7. Differences between women reported and prosecuted and prosecuted and convicted for tax fraud in Serbia

Table 7 indicates that the gap between reported cases and prosecutions was relatively small in 2014, increased to 88 in 2018, and then decreased to 31 in 2021. The difference between the number of women prosecuted and those convicted for tax fraud was 0 in 2016, but over the last three years, this difference ranged from 10 to 16. This highlights the effectiveness of the legal system when women perpetrate crimes.

The Chi-Square for the differences between reported, prosecuted, and convicted women is the same as for the differences for women in economic crime acts: 48, with the degree of freedom being 42. Based on this, we cannot definitively conclude whether to accept or reject the null hypothesis.

Table 8. Chi-Square test results for the difference between reported and prosecuted and prosecuted and convicted women for tax fraud in Serbia

Table 9 presents the criminal sanctions imposed on those convicted of economic crimes. All sanctions are categorised as unconditional imprisonment, suspended sentences, or fines.

In 2014, unconditional imprisonment was imposed on 29.7 % of all individuals convicted of tax crimes. By 2021, this sanction was applied to only 14.7 % of those convicted.

Table 9. Criminal sanctions imposed for tax fraud

Source: Authors’ calculations based on the data from Bulletin of adult criminal offenders in the Republic of Serbia, Serbian Bureau of Statistics

The sentence was suspended for 63.7 % of all individuals in 2014 and 62.18 % of those convicted of tax crimes in 2021. The fine was imposed on 6.25 % of those convicted in 2014, then decreased to 5.4 % in 2021.

Although the sanctions are not categorised by gender, we can infer that women receive similar types of sanctions. Based on this observation, the highest number of women were given suspended sentences, followed by unconditional imprisonment and fines.

Discussion of results

The results of Serbian statistics on economic crime from 2014 to 2021 support our research questions (RQ1). We hypothesised that fewer women are reported, prosecuted, and convicted for economic crimes, and the statistics provide inconclusive evidence regarding this. In 2021, only 12.7 % of reported criminals were women, 14.7 % were prosecuted, and 14.6 % were convicted. This supports our first research question, as it indicates that over 85 % of all economic crime perpetrators were men.

However, we expected that these percentages for women would increase after COVID-19. Surprisingly, following the pandemic, women were less frequently reported, prosecuted, and convicted of economic crimes compared to men. Interestingly, in 2020, the year of the COVID-19 outbreak, a higher percentage of women were reported, prosecuted, and convicted than in any previous year of the observed period, with figures of 17.7 %, 20.1 %, and 16.8 %, respectively.

Our findings regarding tax crimes support research question number 2. Over 87 % of all reported perpetrators of tax crimes were men, and more than 90 % of those who were prosecuted and convicted were also men. This suggests that tax crimes are predominantly committed by male offenders. However, after COVID-19, there was a noticeable decrease in the number of women reported, prosecuted, and convicted for tax crimes compared to the period before the pandemic. Notably, in 2020, the highest percentage of women prosecuted and convicted was 20.1 %, which was an increase from previous periods.

This disparity might be attributed to the effectiveness of the prosecution system and the courts, or it could stem from the fact that tax crimes typically involve individuals with high incomes. Additionally, women may be less involved in these crimes due to their underrepresentation in positions of economic power. Wealthy individuals are more frequently implicated in tax evasion and avoidance, classifying these acts as white-collar crimes primarily associated with the upper echelon of businesspeople. Such crimes often entail more sophisticated methods than other types, like embezzlement. Notably, after 2020, only 8 - 9 % of those prosecuted and convicted for tax fraud were women.

According to Willott and Griffin (1999), men are five times more likely than women to be cautioned or convicted for crimes, yet mainstream criminology lacks explanations for this disparity. In our 2021 findings, for every woman convicted of tax fraud, nine men were convicted, indicating that men are nine times more likely than women to commit tax fraud. Additionally, for economic crimes in 2021, the ratio was even higher, with 13 men convicted for every woman convicted.

One possible explanation is that, in other types of crime, individuals with less power are typically more prone to criminal behaviour. However, in the context of white-collar or economic crime in Serbia, women, despite having less power than men, are actually less likely rather than more likely to engage in criminal activities.

The Centre for Investigative Journalism of Serbia (https://www.cins.rs/poreska-utaja-zlocin-koji-se-isplati/) reports that more than two-thirds of tax fraud cases in Serbia result in a guilty plea. When examining women’s motivations for committing crimes, studies indicate that women are often driven to crime by the need to provide for their families or maintain relationships with partners and husbands (Daly, 1989). This suggests that gender could serve as a moderating variable influencing the relationship between justice, culture, the desire for wealth, and the ethical perception of tax evasion (Ariyanto et al., 2020). Furthermore, Charris-Peláez et al. (2022) found that female offenders require specific treatment tailored to their unique criminal profiles and the particular needs associated with their gender. Future research in this field should focus on the specialised support women need when facing criminal charges.

These results can be compared with those from neighbouring countries such as Croatia and Montenegro. In Croatia, studies indicate that women are more likely to commit specific types of economic crimes, with reports showing that 18 % of such cases involved women (Kalac & Bezić, 2023). This percentage is higher than that in Serbia, where it ranges from 12 % to 16 %. However, the data for Montenegro differs, making a direct comparison difficult.

Croatia’s statistics reveal a notable trend regarding economic criminal acts. The percentage of reported female perpetrators for confidence abuse in business operations increased from approximately 30 % in 2016 to 34 % in 2020. As a member of the European Union, Croatia has a better position on gender equality compared to Serbia. This environment seems to enable women in power to adopt behaviours similar to their male counterparts, resulting in higher rates of involvement in criminal networks. In contrast, data from Montenegro indicate that economic crime ranks significantly among women, often placing third or fourth each year. This suggests that women in Montenegro are more likely to engage in such crimes when they face economic resource deprivation, a situation that is prevalent in Montenegro.

There is currently no conclusive evidence to suggest that increasing gender equality or placing women in more powerful positions within businesses can prevent economic criminality. In fact, Steffensmeier et al. (2013) found that as women advance in the labour market and gain upward mobility, the differences in criminal behaviour between genders diminish. When gender equality is implemented, it can result in more women participating in this type of criminal activity. That is in line with Kirsch’s (2007) remark that, regarding personal traits, female CEOs might have more in common with their male counterparts than with women in general.

Conclusion and recommendation

Tax fraud is an important issue because it can result in a significant loss of revenue for society. It is argued that tax fraud is determined by individual cognitive, organisational, and Fraud Diamond factors in corporate tax fraud (Azrina Mohd Yusof & Ling Lai 2014). Since women are taking a steeply increasing share of leadership roles in the corporate world (Brieger et al., 2019; Pavlović et al., 2023), research on the gender role in business activities, including corporate fraud, is increasing, too. Contemporary literature highlights biological and psychological differences between males and females, linking risk aversion and ethical sensitivity to key accounting issues like conservatism in financial reporting and opposition to fraud. (Cumming et al., 2015; Ho et al., 2015; Pavlović et al., 2018).

The manuscript focuses on investigating secondary data concerning economic crime and tax fraud within the Serbian economy. It aims to answer whether women are less reported, prosecuted, and convicted for these offenses. The statistics indicate that 85 % of those who commit economic crimes are men, with over 90 % of them engaging in tax fraud. While women generally hold less power, they also tend to show less willingness to commit these crimes, resulting in lower rates of prosecution and conviction.

After COVID-19, the percentage of women being convicted and prosecuted for tax fraud is 8 - 10 %, while 15 % face charges for economic crime. One possible explanation is that women tend to commit embezzlement, which is a simpler crime, whereas they are less frequently involved in more complex cases of economic crime and tax fraud.

It is important for the government to recognise that achieving gender equality in Serbia will not necessarily decrease women’s involvement in criminal activity. In fact, it is likely that more crimes will be committed by women in the future. The government should focus on raising awareness that “crime does not pay.”

A comparison of women who have been reported, prosecuted, and convicted indicates that the legal and prosecution systems in Serbia are effective, particularly in cases of economic crime, a trend that has been evident since 2018. However, beyond this efficiency, the legal system needs to impose stricter penalties for economic crimes to deter individuals of all genders from engaging in criminal behaviour. Furthermore, it appears that judges in Serbia tend to be less inclined to impose severe punishments for economic crimes. This trend suggests a need for a more consistent approach to sentencing in order to effectively combat these offenses.

Future researchers could explore the link between gender equality and economic crimes committed by women in various countries to address the existing gap in this field. Furthermore, it should be examined whether the age of decision-makers significantly influences the occurrence of economic crimes since it is well-known that personal traits change over time.

Conflict of interest

There was no conflict of interest between the authors of this academic research. We declare that we do not have any financial or personal relationship that could influence the interpretation and publication of the results obtained. Likewise, we ensure that we comply with ethical standards and scientific integrity at all times, in accordance with the guidelines established by the academic community and those dictated by this journal.

References

Agnew R., Piquero N. L., & Cullen F. T. (2009). General strain theory and white-collar crime. In Simpson S. S., Weisburd D. (Eds.), The criminology of white-collar crime (pp. 35-60). Springer.

Agnew, R. (2013). When criminal coping is likely: An extension of general strain theory. Deviant Behavior, 34(8), 653–670. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2013.766529

Agnew, R. (2015). Strain, economic status, and crime. In A. R. Piquero (Ed.), The Handbook of Criminological Theory (pp. 209-229). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118512449.ch11

Agnew, R., & Brezina, T. (2010). Strain theories. In E. McLaughline & T. Newburn (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of criminological theory (pp. 96-113). Sage Publications.

Agnew, R., & White, H. R. (1992). An empirical test of general strain theory. Criminology, 30(4), 475-500.

Agnew, R., & Brezina, T. (2019). General strain theory. In M. Krohn, N. Hendrix, G. Penly Hall, & A. Lizotte (Eds.), Handbook on Crime and Deviance (pp. 145-160). Springer.

Al-Badayneh, D. M., Ben Brik, A., & Elwakad, A. (2024). A partial empirical test of the general strain theory on cyberbullying victimization among expatriate students. Journal of Criminological Research, Policy and Practice, 10(1), 35-52. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCRPP-03-2023-0013

Albanese, J. (2021). Organized Crime vs. White-collar crime: which is the bigger problem? Academia Letters, Article 310. https://doi.org/10.20935/AL310

Amara, I., & Khlif, H. (2018). Financial crime, corruption and tax evasion: A cross-country investigation, Journal of Money Laundering Control, 21(4), 545-554. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMLC-10-2017-0059

Argentiero, A., Chiarini, B., & Marzano, E. (2020). Does tax evasion affect economic crime? fiscal studies. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-5890.12214

Ariyanto, D., Weni Andayani, G. A. P., & Dwija Putri, I. G. A. M. A. (2020). Influence of justice, culture and love of money towards ethical perception on tax evasion with gender as moderating variable. Journal of Money Laundering Control, 23(1), 245-266.

Ashforth, B. E., & Anand, V. (2003). The normalization of corruption in organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior, 25, 1-52. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-3085(03)25001-2

Azrina Mohd Yusof, N., & Ling Lai, M. (2014). An integrative model in predicting corporate tax fraud, Journal of Financial Crime, 21(4), 424-432. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFC-03-2013-0012

Baumann, F., & Friehe, T. (2015). Status concerns as a motive for crime?. International Review of Law and Economics, 43, 46-55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irle.2015.05.001

Benson, M.L., Madensen, T.D., Eck, J.E. (2009). White-Collar Crime from an Opportunity Perspective. In: Simpson, S.S., Weisburd, D. (eds) The Criminology of White-Collar Crime. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-09502-8_9.

Božić, D., Dimić, S., & Đukić, M (2020). Some issues of processing tax fraud in criminal legislation in the Republic of Serbia. Balkan Social Science Review, 16, 89-107.

Brezina, T. (2017). General strain theory. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Criminology. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264079.013.249

Brieger, S. A., Francoeur, C., Welzel, C., & Ben-Amar, W. (2019). Empowering women: The role of emancipative forces in board gender diversity. Journal of Business Ethics, 155, 495-511.

Broidy, L. M. (2001). A test of general strain theory. Criminology, 39(1), 9-36. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2001.tb00915.x

Bruinsma, G. J. (1992). Differential association theory reconsidered: An extension and its empirical test. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 8, 29-49.

Chan, K. K. (2023). Drivers of Race Crime and the Impact of Bridging Gaps: A Dynamic Empirical Analysis. Race and Social Problems, 15(4), 460-473..https://doi.org/10.1007/s12552-022-09382-3

Charris-Peláez, V. M., Merlano-Villalba, A., Jiménez-Prestan, D., Salas-Manjarrés, A. P., Kleber-Espinosa, J. M., & Quiroz-Molinares, N. (2022). Why women offend?: A gendered approach to criminal behavior, prison context and treatment. Revista Criminalidad, 64(1), 83-94.

Cohen, A. K. (1955). Delinquent Boys. New York: Free Press

Cloward, R. A., & Ohlin, L. E. (1960). Delinquency and Opportunity. New York: Free PressCressey, D. R. (2017). The poverty of theory in corporate crime research. In W. S. Laufer, & F. Adler. (Eds.), Advances in criminological theory (pp. 31-56, 1st Ed. in 1989). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351317566

Cumming, D., Leung, T. Y., & Rui, O. (2015). Gender diversity and securities fraud. Academy of Management Journal, 58(5), 1572-1593.

Daly, K. (1989). Gender and varieties of white‐collar crime. Criminology, 27(4), 769-794.

Daly, K., & Chesney-Lind, M. (1988). Feminism and criminology. Justice Quarterly, 5(4), 497-538. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418828800089871

Davies, P. A. (2003). Is economic crime a man’s game? Feminist Theory, 4(3), 283-303. https://doi.org/10.1177/14647001030043003

DeLisi M., & Vaughn M. G. (2016). Correlates of crime. In A. Piquero (Ed.), The Handbook of Criminological Theory (pp. 18-36). Wiley Blackwell.

DeLisi, M. (2011). How general is general strain theory? Journal of Criminal Justice, 1(39), 1-2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2010.12.003

Dimovski, D. (2023). Women’s Crime in the Republic of Serbia: Research on Judicial Practice in the City of Niš. In The Handbook on Female Criminality in the Former Yugoslav Countries. Springer.

Eme, R. F. (2007). Sex differences in child-onset, life-course-persistent conduct disorder. A review of biological influences. Clinical Psychology Review, 27(5), 607-627.

Feld, L. P., & Frey, B. S. (2002). Trust breeds trust: How taxpayers are treated. Economics of governance, 3(2), 87-99.

Friedrichs, D., Schoultz, I., & Jordanoska, A. (2017). Edwin H. Sutherland (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315406862

Gavrilović, M. (1970). Economic Criminality in Serbia. Yugoslavian J. Crimin. & Crim. L., 8, 358-372.

Golladay, K. A., & Snyder, J. A. (2023). Financial fraud victimization: an examination of distress and financial complications. Journal of Financial Crime, 30(6), 1606-1628.https://doi.org/10.1108/JFC-08-2022-0207

Hindelang, M. J. (1979). Sex differences in criminal activity. Social Problems, 27(2), 143-156.

Hirschi, T., & Gottfredson, M. (1987). Causes of white‐collar crime. Criminology, 25(4), 949-974.

Ho, S. S., Li, A. Y., Tam, K., & Zhang, F. (2015). CEO gender, ethical leadership, and accounting conservatism. Journal of Business Ethics, 127, 351-370.

Huang, W., Chen, X., & Wu, Y. (2024). Education fever and adolescent deviance in China. Crime & Delinquency, 70(10), 2826-2850. https://doi.org/10.1177/00111287231174421

Isom, D. A., Grosholz, J. M., Whiting, S., & Beck, T. (2021). A gendered look at Latinx general strain theory. Feminist Criminology, 16(2), 115-146. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557085120973077

Ji, J., Dimitratos, P., Huang, Q., & Su, T. (2019). Everyday-life business deviance among Chinese SME owners. Journal of Business Ethics, 155, 1179-1194. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3542-2

Jovanović, A., Rakočević, V., & Rakočević, L. (2023). Female Criminality in Montenegro. In The Handbook on Female Criminality in the Former Yugoslav Countries (pp. 163-193). Springer International Publishing.

Jugović, A., Brkić, M. L., & Simeunović-Patić, B. (2008). Social inequality and poverty as a social context of criminality. Godišnjak Fakulteta Političkih Nauka, 2(2), 447-461.

Kalac, A. M. G., & Bezić, R. (2023). Gender and crime in Croatia: Female criminality in context. In The Handbook on female criminality in the former Yugoslav countries (pp. 75-104). Springer International Publishing.

Kabiri, S., Donner, C. M., Maddahi, J., Shadmanfaat, S. M., & Hardyns, W. (2024). How general is general strain theory? An inquiry of workplace deviance in Iran. International Criminal Justice Review, 34(2), 147-164. https://doi.org/10.1177/10575677231172833

Khan, K. A., Metzker, Z., Streimikis, J., & Amoah, J. (2023). Impact of negative emotions on financial behavior: An assessment through general strain theory. Equilibrium. Quarterly Journal of Economics and Economic Policy, 18(1), 219–254. https://doi.org/10.24136/eq.2023.007

Klenowski, P. M., Copes, H., & Mullins, C. W. (2011). Gender, identity, and accounts: How white collar offenders do gender when making sense of their crimes. Justice Quarterly, 28(1), 46-69.

Kim, J., Leban, L., Lee, Y., & Jennings, W. G. (2023). Testing gender differences in victimization and negative emotions from a developmental general strain theory perspective. American journal of criminal justice, 48, 444-462. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-021-09650-9

Klein, D. (1973). The etiology of female crime: A review of the literature. Issues Criminology, 8, 3-30.

Kirsch, A. (2018). The gender composition of corporate boards: A review and research agenda. The Leadership Quarterly, 29(2), 346-364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2017.06.001

Knežević, G. Pavlović, V., & Halil Arıç, H. (2020). Does Tax Evasion Significantly Contribute to Overall Economic Crime in Serbia? FINIZ 2020-People in the focus of process automation (pp. 12-17). https://portal.finiz.singidunum.ac.rs/Media/files/2020/12-17.pdf

Knežević, G., Pavlović, V., & Bojičić, R. (2023). Does gender diversity improve CSR reporting? Evidence from the Central and West Balkan banking sector. Economics & Sociology, 16(3), 261-280. https://doi.org/10.14254/2071-789X.2023/16-3/14

Kondrat, A. G., & Connolly, E. J. (2023). An examination of the reciprocal relations between treatment by others, anger, and antisocial behavior: A partial test of general strain theory. Crime & Delinquency, 69(12), 2595-2613. https://doi.org/10.1177/00111287221087947

Kulić, M., & Milošević, G. (2010). Tax crimes. J. Crimin. & Crim. L., 48, 107.

Kulić, M., & Milošević, G. (2011). Relation of criminal offence of tax evasion and criminal offence of non-payment of withholding tax in Serbian criminal law. Anali Pravnog fakulteta u Beogradu, 59(2), 321-343.

Kulić, M., Milošević, G., & Milašinović, S. (2011). Fiscal crime in Serbia. Industrija, 39(4), 293-306.

Larsson, B. (2001). What is ‘‘economic’’ about ‘‘economic crime? In S. A. Lindgren (Ed.), White-collar crime research: Old views and future potentials (pp. 121-136). The National Council for Crime Prevention.

Le Maux, J., & Smaili, N. (2023). Fighting against white-collar crime: Criminology to the aid of management sciences. Journal of Financial Crime, 30(6), 1595-1605. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFC-07-2022-0165

Levi, M. (2015). Foreword: Some reflections on the evolution of economic and financial crimes. In B. Rider (Ed.), Research Handbook on International Financial Crime. Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

Man, P. K., & Cheung, N. W. (2022). Do gender norms matter? General strain theory and a gendered analysis of gambling disorder among Chinese married couples. Journal of Gambling Studies, 38(1), 123-151. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-021-10021-6

Matsueda, R. L. (2001). Differential association theory. Encyclopedia of Criminology and Deviant Behavior, 1, 125-130.

Melis-Rivera, C., & Piñones-Rivera, C. (2023). Criminology and identity: A theoretical review. Revista Criminalidad, 65(3), 65-79. https://doi.org/10.47741/17943108.523

Merton, R. (1938). Social Structure and Anomie. American Sociological Review, 3(5), 672-682. https://doi.org/10.2307/2084686

Mitrović, M. (2006). Current social conflicts and criminality in Serbia. Zbornik Matice srpske za drustvene nauke, (120), 114-128.

Morgan, S., Allison, K., & Klein, B. R. (2024). Strained Masculinity and Mass Shootings: Toward A Theoretically Integrated Approach to Assessing the Gender Gap in Mass Violence. Homicide Studies, 28(4), 441-467. https://doi.org/10.1177/10887679221124848

Opp, K.D. (1974). Abweichendes Verhalten und Gesellschaftsstruktur, Luchterhand, Neuwied.Passas, N. (2017). Globalization, criminogenic asymmetries and economic crime. In International crimes (pp. 17-42). Routledge.

Pavićević, O. (2020). Kriminalizacija marginalizovanih žena. Zbornik Instituta za kriminološka i sociološka istraživanja, 39(2-3), 59-73.

Pavićević, O., & Bulatović, A. (2018). Žene u organizovanom kriminalu. Zbornik Instituta za kriminološka i sociološka istraživanja, 37(1), 85-101.

Pavlović, V., Knežević, G., & Bojičić, R. (2018). Board gender diversity and earnings management in agricultural sector - Does it have any influence. Custos e Agronegócio on line, 14, 340-363.

Pavlović, V., Knežević, G., & Bojičić, R. (2022). The impact of gender and age on earnings management practices of public enterprises: A case study of Belgrade, Economic Studies (Ikonomicheski Izsledvania), 31(3), 130-148.

Pavlović, V., Knežević, G., & Bojičić, R. (2023). Do the profitability, the volume of assets, and equity of public enterprises have any role in local authorities’ gender and age policy? - A case study of Belgrade, Economic Studies (Ikonomicheski Izsledvania), 32(2), 174-193.

Reurink, A. (2016). “White-Collar Crime”: The concept and its potential for the analysis of financial crime. European Journal of Sociology/Archives Européennes de Sociologie, 57(3), 385-415.

Robinson, M. (2006). The integrated systems theory of antisocial behavior. In The Essential Criminology Reader (pp. 319-335). Routledge.

Robinson, M. (2014). Three: Why do people commit crime? An integrated systems perspective. In Applying complexity theory (pp. 59-78). Policy Press. https://doi.org/10.51952/9781447311416.ch003

Scaptura, M. N., Boyle, K. M., & Rogers, K. B. (2024). Subordination to Women, Anger, and Endorsement of Violence Against Women: A Test of General Strain Theory. Feminist Criminology, Early Access. https://doi.org/10.1177/15570851241274863

Simović, M. N., Jovašević, D., & Simović, V. M. (2017). Tax Crimes In The Law Practice Of Republic Of Serbia. Journal of International Scientific Publications: Economy & Business, 11(1), 87-105.

Simpson, S. S., & Weisburd, D. (Eds.). (2009). The criminology of white-collar crime (vol. 228). Springer.

Slemrod, J. (2007). Cheating ourselves: The economics of tax evasion. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21(1), 25-48.

Steffensmeier, D. J., Schwartz, J., & Roche, M. (2013). Gender and twenty-first-century corporate crime: Female involvement and the gender gap in Enron-era corporate frauds. American Sociological Review, 78(3), 448-476.

Saluja, S., Aggarwal, A., & Mittal, A. (2022). Understanding the fraud theories and advancing with integrity model. Journal of Financial Crime, 29(4), 1318-1328. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFC-07-2021-0163

Sutherland, E. H. (1940). White-collar criminality. Sociological Review, 5(1), 1-12.

Sutherland, E.H. (1947) Principles of Criminology (4th Ed.), Philadelphia,J.B. Lippincott Company.

Svensson, B. (1984). Economic crime in Sweden. Information Bulletin of the National Swedish Council for Crime Prevention.

Tickner, P., & Button, M. (2021). Deconstructing the origins of Cressey’s Fraud Triangle. Journal of Financial Crime, 28(3), 722-731. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFC-10-2020-0204

Tittle, C. R. (2016). Introduction: Theory and contemporary criminology. In A. R. Piquero (Ed.), The Handbook of Criminological Theory (pp. 1-17). Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118512449.ch1

Tupman, W. (2015). The characteristics of economic crime and criminals. In Research Handbook on International Financial Crime (pp. 3-14). Edward Elgar PublisGrahing.

UNODC. (2005). Economic and financial crimes: Challenges to sustainable development. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

Willott, S., & Griffin, C. (1999). Building your own lifeboat: Working‐class male offenders talk about economic crime. British Journal of Social Psychology, 38(4), 445-460.

Wallace, C., & Pahl, R. (1986). Polarisation, Unemployment and All Forms of Work1. In The experience of unemployment (pp. 116-133). Palgrave Macmillan UK

Zavala, E., Perez, G., & Sabina, C. (2024). Explaining Latinx youth delinquency: A gendered test of Latinx general strain theory. Race and Justice, 14(2), 190-216.https://doi.org/10.1177/21533687211047931